Reasoning about systems of linear equations using linear algebra

Published:

In this blog post, we will discuss the relationship between matrices and systems of linear equations. Specifically, we will show how systems of linear equations can be represented as a single matrix equation. Solutions to the system of linear equations can be reasoned about by examining the characteristics of the matrices and vectors in that matrix equation.

Introduction

In this blog post, we will discuss the relationship between matrices and systems of linear equations. Specifically, we will show how systems of linear equations can be represented as a single matrix equation. Solutions to the system of linear equations can be reasoned about by examining the characteristics of the matrices and vectors involved in that matrix equation.

Systems of linear equations

A system of linear equations is a set of linear equations that all utilize the same set of variables, but each equation differs by the coefficients that multiply those variables.

For example, say we have three variables, $x_1, x_2$, and $x_3$. A system of linear equations involving these three variables can be written as:

\[\begin{align*}3 x_1 + 2 x_2 - x_3 &= 1 \\ 2 x_1 + -2 x_2 + 4 x_3 &= -2 \\ -x_1 + 0.5 x_2 + - x_3 &= 0 \end{align*}\]A solution to this system of linear equations is an assignment to the variables $x_1, x_2, x_3$, such that all of the equations are simultaneously true. In our case, a solution would be given by $(x_1, x_2, x_3) = (1, -2, -2)$.

More abstractly, we could write a system of linear equations as

\[\begin{align*}a_{1,1}x_1 + a_{1,2}x_2 + a_{1,3}x_3 &= b_1 \\ a_{2,1}x_1 + a_{2,2}x_2 + a_{2,3}x_3 &= b_2 \\ a_{3,1}x_1 + a_{3,2}x_2 + a_{3,3}x_3 &= b_3 \end{align*}\]where $a_{1,1}, \dots, a_{3,3}$ are the coefficients and $b_1, b_2,$ and $b_3$ are the constant terms, all treated as fixed. By “fixed”, we mean that we assume that $a_{1,1}, \dots, a_{3,3}$ and $b_1, b_2,$ and $b_3$ are known. In contrast, $x_1, x_2,$ and $x_3$ are unknown. We can try different values for $x_1, x_2,$ and $x_3$ and test whether or not that assignment is a solution to the system.

Reasoning about the solutions to a system of linear equations by respresenting the system as a matrix equation

Now, a natural question is: given a system of linear equations, how many solutions does it have? Will a system always have a solution? If did does have a solution will it only be one solution? We will use concepts from linear algebra to address these questions.

First, note that we can write a system of linear equations much more succinctly using matrix-vector multiplication. That is,

\[\begin{bmatrix}a_{1,1} && a_{1,2} && a_{1,3} \\ a_{2,1} && a_{2,2} && a_{2,3} \\ a_{3,1} && a_{3,2} && a_{3,3} \end{bmatrix} \begin{bmatrix}x_1 \\ x_2 \\ x_3\end{bmatrix} = \begin{bmatrix}b_1 \\ b_2 \\ b_3\end{bmatrix}\]If we let the matrix of coefficients be $\boldsymbol{A}$, the vector of variables be $\boldsymbol{x}$, and the vector of constants be $\boldsymbol{b}$, then we could write this even more succinctly as:

\[\boldsymbol{Ax} = \boldsymbol{b}\]This is an important point: any system of linear equations can be written succintly as an equation using matrix-vector multiplication. By viewing systems of linear equations through this lense, we can reason about the number of solutions to a system of linear equations using properties of the matrix $\boldsymbol{A}$!

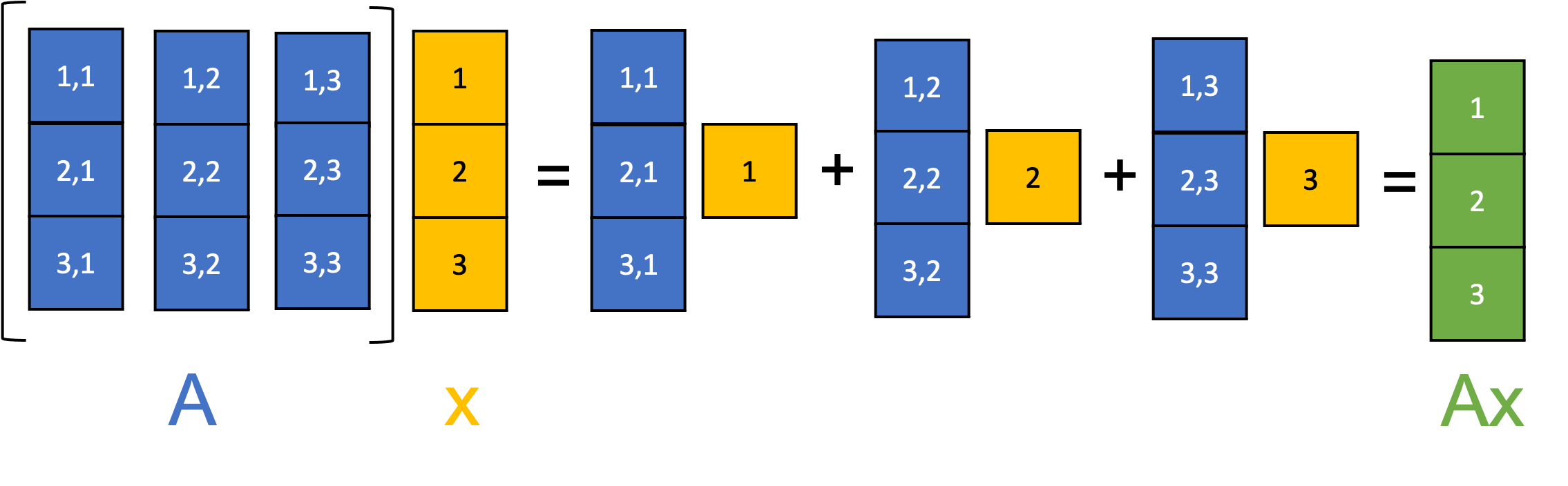

Given this newfound representation for systems of linear equations, recall from our discussion of matrix-vector multiplication, a matrix $\boldsymbol{A}$ multiplying a vector $\boldsymbol{x}$ can be understood as taking a linear combination of the column vectors of $\boldsymbol{A}$ using the elements of $\boldsymbol{x}$ as the coefficients:

Thus, we see that the solution to a system of linear equations, $\boldsymbol{x}$, is any set of weights for which, if we take a weighted sum of the columns of $\boldsymbol{A}$, we get the vector $\boldsymbol{b}$. That is, $\boldsymbol{b}$ is a vector that lies in the span of the columns of $\boldsymbol{A}$!

From this observation, we can begin to draw some conclusions about the number of solutions a given system of linear equations will have based on the properties of \(\boldsymbol{A}\). Specifically, the system will either have:

- No solution. This will occur if \(\boldsymbol{b}\) lies outside the span of the columns of $\boldsymbol{A}$. This means that there is no way to construct $\boldsymbol{b}$ from the columns of $\boldsymbol{A}$, and thus there is no weights-vector $\boldsymbol{x}$ that will satisfy the equation $\boldsymbol{Ax} = \boldsymbol{b}$. Note, this can only occur if $\boldsymbol{A}$ is singular. Why? Recall that an invertible matrix maps each inpu vector $\boldsymbol{x}$ to a unique output vector $\boldsymbol{b}$ and each output $\boldsymbol{b}$ corresponds to a unique input $\boldsymbol{x}$. Said more succintly, an invertible matrix characterizes a one-to-one and onto linear tranformation. Therefore, if $\boldsymbol{A}$ is invertible, then for any given $\boldsymbol{b}$, there must exist a vector, $\boldsymbol{x}$, that solves the equation $\boldsymbol{Ax} = \boldsymbol{b}$. If such a vector does not exist, then $\boldsymbol{A}$ must not be invertible.

- Exactly one solution. This will occur if $\boldsymbol{A}$ is invertible. As discussed above, an invertible matrix characterizes a one-to-one and onto linear transformation and thus, for any given $\boldsymbol{b}$, there will be exactly one vector, $\boldsymbol{x}$, that solves the equation $\boldsymbol{Ax} = \boldsymbol{b}$.

- Infinitely many solutions. This will occur if $\boldsymbol{b}$ lies inside the span of the columns of $\boldsymbol{A}$, but $\boldsymbol{A}$ is not invertible. Why would there be an infinite number of solutions? Recall that if $\boldsymbol{A}$ is not invertible, then the columns of $\boldsymbol{A}$ are linearly dependent, meaning that there are an infinite number of ways to take a weighted sum of the columns of $\boldsymbol{A}$ to get $\boldsymbol{b}$. Thus, an infinite number of vectors that satisfy $\boldsymbol{Ax} = \boldsymbol{b}$.