Expectation-maximization: theory and intuition

Published:

Expectation-maximization (EM) is a popular algorithm for performing maximum-likelihood estimation of the parameters in a latent variable model. In this post, I discuss the theory behind, and intuition into this algorithm.

Introduction

Expectation-maximization (EM) is a popular algorithm for performing maximum-likelihood estimation of the parameters in a latent variable model. Introductory machine learning courses often teach the variants of EM used for estimating parameters in important models such as Guassian Mixture Models and Hidden Markov Models. EM also features heavily in bioinformatics where, for example, it is used for quantifying gene expression from RNA-sequencing data and for finding sequence-motifs in genomes.

After learning about this algorithm in introductory graduate school courses, the intuition was clear, but I still had several remaining questions. When is EM preferred over some other method for estimating parameters? What is EM really doing? Why is EM guaranteed to converge?

In this blog post, I’ll describe my current understanding of the theory behind the EM algorithm, which helped me to answer the aformentioned questions. I’ll also offer a few perspectives for intuiting this algorithm.

The Setting

As mentioned previously, EM is used for performing maximum likelihood estimation on the parameters of a latent variable model. To review this task, let’s say we have two sets of random variables $X$ and $Z$ and some parameterized joint distribution over these random variables:

\[p(x, z; \theta)\]where $p$ is the probability mass/density function, $x$ and $z$ are values for $X$ and $Z$, and $\theta$ parameterizes the distribution.

Further, we assume that we have observed $x$, the value of $X$, but have not observed $z$, the value of $Z$. Despite not observing $z$, we wish to find the value for $\theta$ that makes $x$ most likely under our model. Since we have not observed z, our likelihood function must marginalize over z:

\[l(\theta) := \log p(x ; \theta) = \log \int p(x, z ; \theta) \ dz\]In practice, maximizing this function over θ may be difficult to do analytically due to this integral. For such situations, the EM algorithm may provide a method for computing a local maximum of this function with respect to θ.

Description of EM

The EM algorithm alternates between two steps: an expectation-step (E-step) and a maximization-step (M-step). Throughout execution, the algorithm maintains an estimate of the parameters $\theta$ that is updated on each iteration. As the algorithm progresses, this estimate of $\theta$ converges to a local maximum of $l(\theta)$. Let $t$ denote a given step of the algorithm. On the $t$th step, we’ll denote $\theta_t$ as the $t$th estimate of $\theta$.

Each step works as follows: On the $t$th E-step, the algorithm formulates a function of $\theta$ called the Q-function, denoted $Q_t(\theta)$. Then, on the next M-step, the algorithm assigns $\theta_{t+1}$ to be the value that maximizes $Q_t(\theta)$.

This alternation between formulating a Q-function and maximizing that Q-function are repeated until the estimate of $\theta$ converges. As we will prove later, not only is this process guaranteed to converge, but it will converge to a local maximum of $l(\theta)$.

More specifically, the E-Step and M-Step work as follows:

E-Step

Compute the conditional probability $p(z \mid x ; \theta_t)$. From this calculation, formulate the Q-function:

\[\begin{align*}Q_t(\theta) &:= E_{Z\mid x, \theta_t}\left[ \log p(x, z ; \theta) \right] \\ &= \int p(z \mid x ; \theta_t) \log p(x,z ; \theta) \ dz \end{align*}\]The “core” of formulating an EM algorithm for a particular model is calculating $p(z \mid x ; \theta_t)$. If the model admits an easy calculation of this function, then the EM algorithm may be a good a choice!

M-Step

Assign $\theta_{t+1}$ to be the value that maximizes the Q-function that was formulated on the previous E-step:

\[\theta_{t+1} := \text{arg max}_\theta Q_t(\theta)\]We repeat the E-Step and M-Step until the difference between $\theta_t$ and $\theta_{t+1}$ is small, indicating convergence. We also note that $\theta_0$ can be set to an arbitrary value – usually set randomly. Since EM finds a local maximum of $l(\theta)$, it is often wise to try many different $\theta_{0}$’s!

EM is coordinate ascent on the evidence lower bound

Now, let’s dig into what the EM algorithm is really doing. Specifically, we will show that EM is a coordinate ascent algorithm on a quantity called the evidence lower bound (ELBO).

Coordinate ascent? ELBO? Before talking about EM, let’s first dig into the these concepts:

The evidence lower bound

For a thorough discussion regarding the evidence lower bound, see my blog post. To review this discussion, if we happen to know (or posit) that $Z$ follows some distribution $q(z)$ (and that $p(x, z; \theta) := p(x \mid z ; \theta)q(z)$), then the evidence lower bound (ELBO) is a lower bound on the likelihood function:

\[\log p(x ; \theta) \geq \text{ELBO} := E_{Z \sim q}\left[\log \frac{p(x,Z; \theta)}{q(Z)} \right]\]Coordinate ascent

Coordinate ascent is a relatively simple and iterative strategy for maximizing a function. Given a function $f(a, b)$ that takes two arguments $a$ and $b$, the idea of coordinate ascent is that we will iteratively fix $a$ to some value $\hat{a}$ and then choose for $b$ the value $\hat{b}$ that maximizes $f(\hat{a}, b)$ . Given $\hat{b}$, we then re-assign to $a$ the value that maximizes $f(a, \hat{b})$. This procedure is repeated until convergence.

Coordinate ascent on the evidence lower bound

In our setting, we don’t yet know which value to use for $\theta$, nor do we know the distribution $q$ for $Z$. Thus, the ELBO becomes a function of both $q$ and $\theta$:

\[F(q, \theta) := E_{Z \sim q}\left[\log \frac{p(x,Z; \theta)}{q(Z)} \right]\]EM is just coordinate ascent on this function. In the E-Step, we fix $\theta$ and solve for $q$. In the M-Step, we fix $q$ and solve for $\theta$.

First, let’s fix $\theta$ to $\theta_t$ (our current value for $\theta$) and solve for $q$:

\[\begin{align*}\text{argmax}_q \ F(q, \theta_t) &= \text{argmax}_q \ \ E_{z \sim q}\left[ \log \frac{p(Z, x ; \theta)}{q(Z)} \right] \\ &= \text{argmin}_q \ \text{KL}( q(z) \ || \ p(z \mid x ; \theta_t)) \\ &= p(z \mid x ; \theta_t)\end{align*}\]I skipped over several steps in the derivation, but the idea is that maximizing the ELBO with respect to $q$ is equivalent to finding a $q$ that minimizes the KL-divergence (a measure of dissimilarity between two distributions, but not discussed here) between $q(z)$ and $p(z \mid x ; \theta_t)$. The $q$ to do this, is simply $p(z \mid x ; \theta_t)$ itself. Notably, computing $p(z \mid x ; \theta_t)$ is exactly what is needed to formulate the Q-function in the E-Step!

Next, if we hold $q$ fixed to $q_t := p(z \mid x ; \theta_t)$, we see that maximizing $F(q_t, \theta)$ with respect to $\theta$ is equivalent to maximizing the Q-function:

\[\begin{align*}\text{argmax}_{\theta} \ F(q_t, \theta) &= \text{argmax}_{\theta} \ \ E_{z \sim q}\left[ \log \frac{p(Z, x ; \theta)}{p(z \mid x ; \theta_t)} \right] \\ &= \text{argmax}_{\theta} \ \ E_{Z\mid x, \theta_t}\left[ \log p(x, z ; \theta) \right]\end{align*}\]The last line in the above derivation is simply maximzing the Q-function – exactly the M-Step!

Visualizing EM

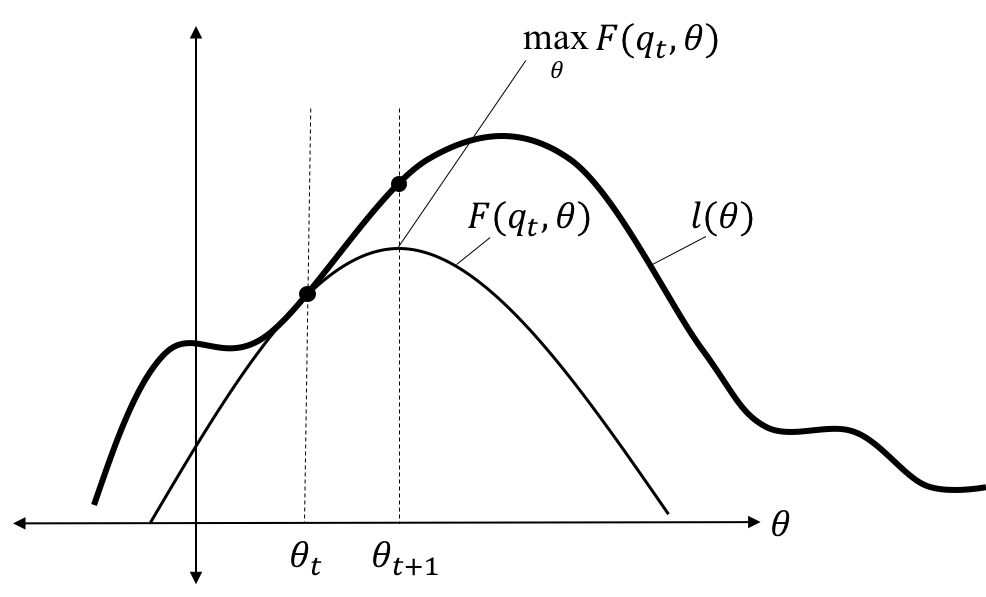

To build up a visual depiction of how the EM algorithm works, we’ll first lay out some relationships between $F$ and $l$:

First, though not proven here, at iteration $t$, the function $F$ touches the likelihood function $l$ at precisely $\theta_t$. That is,

\[F(q_t, \theta_t) = l(\theta_t)\]Second, with $q$ fixed at $q_t$, the function $F$ at $\theta_{t+1}$ will be greater than at $\theta_t$. That is,

\[F(q_t, \theta_{t+1}) \geq F(q_t, \theta_t)\]This follows from the fact that $\theta_{t+1}$ maximizes $F(q_t, \theta)$, by design of the algorithm.

With $q$ fixed at $q_t$, $F$ is bounded from above by $l$. This follows from the fact that $F$ is the the evidence lower bound – that is, it is a lower bound for $l$:

\[F(q_t, \theta) \leq l(\theta)\]These properties are depicted below:

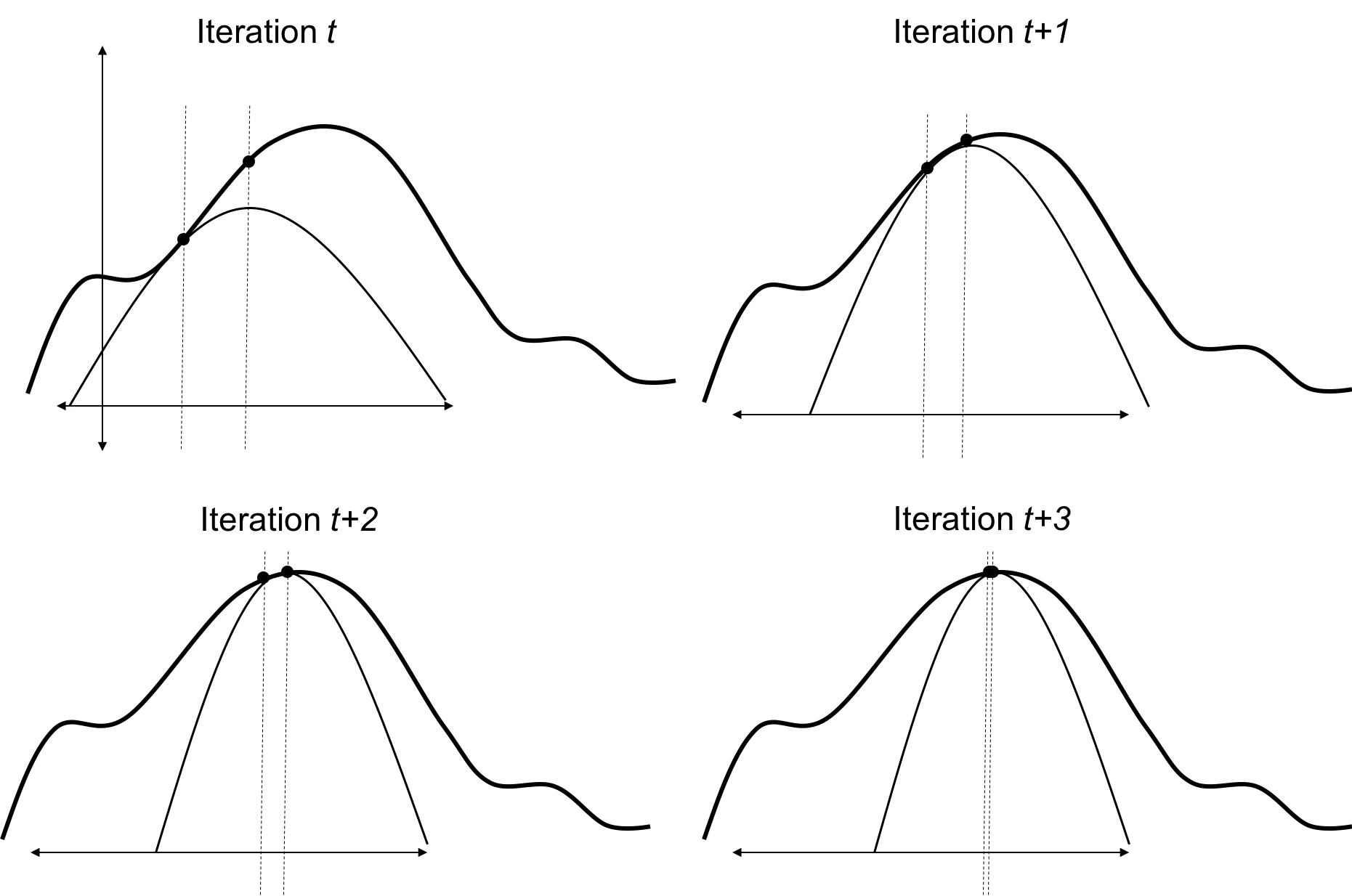

Given these properties, we can reason that EM converges on a local maximum of $l(\theta)$ by “crawling” up the likelihood surface. That is, on each iteration $t$, $F(q_t,\theta)$ lies at or below the likelihood surface, but touches it at $\theta_t$. That is, $F(q_t, \theta_t) = l(\theta_t)$. Then, since $F(q_t, \theta_{t+1}) > F(q_t, \theta_t)$, it follows that $\theta_{t+1}$ increases the likelihood function. Furthermore, on the next iteration, we can evaluate the likelihood function at $\theta_{t+1}$ via $F(q_{t+1}, \theta_{t+1})$. Thus, each proceeding iteration’s value of $F(q_{t+1}, \theta_{t+1})$ is a new, higher value on the likelihood surface than the current value. This process is depicted below:

When to use the EM algorithm

The EM algorithm is just one choice of many for tackling the optimization problem:

\[\text{argmax}_\theta \log p(x; \theta)\]When would EM be preferred over other optimization algorithms out there?

First, the EM algorithm might be a good choice when $l(\theta)$ is challenging to optimize, but the Q-function is easier. The likelihood function is often difficult to optimize due to the presence of the log of an integral:

\[l(\theta) := \log \int p(x, z ; \theta) \ dz\]Taking the derivative/gradient of this function with respect to $\theta$, setting it to zero, and then solving for $\theta$ is often very difficult to do analytically.

On the otherhand, if the integral and logarithm were flipped, then function might be much easier to optimize analytically. The Q-function is just such a function:

\[Q_t(\theta) := \int f(z) \log p(x,z ; \theta) \ dz\]where $f(z) := p(z \mid x ; \theta_t)$.

Thus, we see that EM converts a difficult optimiziation problem into a series of easier optimization problems where each sub-problem is made easier by flipping the integral and log within the objective function!

Intuition behind the Q-function: a generalization of the likelihood function

In the case in which $Z$ is a discrete random variable, the Q-function can be interpreted as a “generalized” version of the complete data likelihood function. First, let’s say that both $X$ and $Z$ are observed where $X = x$ and $Z = z$. Then, we could write the complete data likelihood as

\[\log p(x, z; \theta) := \sum_{z' \in \mathcal{Z}} \mathbb{I}(z=z') \log p(x, z' ; \theta)\]where $\mathcal{Z}$ is the support of $Z$’s probability mass function and $\mathbb{I}(z=z’)$ is an indicator function that equals one when $z’ = z$ and equals zero otherwise.

Now, recall the Q-function:

\[Q_t(\theta) := \sum_{z'} p(z' \mid x ; \theta) \log p(x, z' ; \theta)\]We note that the difference between these two functions is that the indicator variable in the complete data likelihood $\mathbb{I}(z=z’)$ is replaced by the probability $p(z \mid x ;\theta)$. This leads us to viewing the Q-function as a sort of generalization of the complete data likelihood. That is, $p(z \mid x ; \theta)$ acts as a weight for its corresponding term in the summation, and measures our current certainty that the hidden data is equal to $z′$. When we know $Z = z$, all of the weight is assigned to the term in which $z′ = z$ and no weight is assigned to the terms in which $z′ \neq z$ – that is, $p(z \mid x ;\theta)$ reduces to the indicator function.

Intuition behind the Q-function: a likelihood function over a hypothetical dataset

Another way to view the Q-function is as a complete data likelihood function over a hypothetical dataset where this hypothetical dataset is generated from a distribution that depends on our current best guess of $\theta$ (i.e. $\theta_t$ at the $t$th iteration).

That is, let us assume that we generate a very large set of values for $Z$ drawn i.i.d. from the distribution specified by $p(z \mid x ; \theta_t)$:

\[z'_1, z'_2, \dots, z'_n \sim p(z \mid x ; \theta_t)\]For each $z’_i$, we create a new “sub”-dataset $(x, z’_i)$. Note that the observed data $x$ is duplicated in each of these sub-datasets. We then merge all of the datasets $(x, z’_1), . . . , (x, z’_n)$ to form our new hypothetical dataset. Then, the likelihood over these data is

\[l'(\theta) := \prod_{i=1}^n p(x, z'_i ; \theta)\]Now we will show that maximizing the Q-function is equivalent to maximizing this likelihood function over the hypothetical data. Let

\[Z' := \{z'_1, z'_2, \dots, z'_n\}\]Now let $c(z)$ be the cardinality of

\[\{ z' \in Z' \mid z' = z \}\]That is, $c(z)$ is the number of items in $Z’$ that equal $z$. As $n$ approaches infinity then

\[\frac{c(z)}{\sum_{z^*}c(z^*)} = p(z \mid x ; \theta_t)\]Finally we can formulate our maximum likelihood problem on this hypothetical data:

\[\begin{align*}\text{argmax}_\theta \ l'(\theta) &:= \text{argmax}_\theta \ \prod_{i=1}^n p(x, z'_i ; \theta) \\ &= \text{argmax}_\theta \ \prod_{z \in \mathcal{Z}} p(x, z ; \theta)^{c(z)} \\ &= \text{argmax}_\theta \ \sum_{z \in \mathcal{Z}} \frac{c(z)}{\sum_{z^*}c(z^*)} \log p(x, z ; \theta) \\ &= \text{argmax}_\theta \ \sum_{z \in \mathcal{Z}} p(z \mid x ; \theta_t) \log p(x, z ; \theta)\end{align*}\]The final line in the above calculation is the Q-function!

In this light, we can view the EM algorithm as an iterative process, in which we posit a distribution over the hidden data $p(z \mid x ; \theta_t)$, then generate a hypothetical data set on which we perform maximum likelihood estimation. This new estimate of the parameters, as estimated from the hypothetical dataset, is then used in the next iteration to generate another data set. This process is repeated until the estimates of the parameters converge.