What is information? (Foundations of information theory: Part 1)

Published:

The mathematical field of information theory attempts to mathematically describe the concept of “information”. In this series of posts, I will attempt to describe my understanding of how, both philosophically and mathematically, information theory defines the polymorphic, and often amorphous, concept of information. In this first post, I will describe Shannon’s self-information.

Introduction

Information theory is a mathematical theory for describing “information” invented by the late Claude Shannon. Information theory is a fundamental mathematical theory that touches many fields, from statistics to physics. Thus, it is introduced in many introductory college courses.

Strikingly, I found that whenever information theory was taught to me in these courses, the teacher always skipped over what to me seemed to be the most fundamental question of all: what exactly is “information”? It seemed quite strange to learn a theory without defining the subject of that theory!

One reason I think this question is avoided is because we don’t really have a good definition for “information.” This is evidenced by the fact that there is an entire field of philosophy dedicated to the construction of such a definition.

However, despite the fact that humans can’t quite figure out what we mean when we use the word “information”, information does indeed have a rigorous definition within the mathematical field of information theory. Not only is this definition practically useful, I also find it intellectually satisfying.

Information as a measure of surprise

Information theory considers information to be an event that elicits “surprise” in the agent that observes the event. Intuitively, if an event is “surprising”, then we gained more information from the event than if the event had been something we were expecting. In essence, a surprising event changes our understanding of the world whereas an expected event supports our current understanding. We see that intuitively “surprise” is a good measure of the information content of an event. Moreover, if an event is “surprising”, then presumably, this event is considered unlikely – that is, to have a low probability of occuring. Thus, the definition for self-information is built upon probability theory.

From this description, we can think of information as a positive function $I$, often called self-information that acts on probabilities:

\[I : [0,1] \rightarrow [0,\infty)\]Following our intuition that $I$ should describe “surprise”, there are five properties that we would like $I$ to have:

- Surprise is continuous. We would like $I$’s domain to be continuous in the interval $[0,1]$. That is, a small change in the probability of an event should lead to a corresponding small change in the surprise that we experience.

- Surprise is non-negative. Intuitively, the idea of “negative surprise” does not make much sense. Either we aren’t surprised at all, and $I(p) = 0$, or we are surprised and thus $I(p) > 0$.

- Self-information should be monotonic. If we have two probabilities $p_1$ and $p_2$ for which $p_1 < p_2$, then the event associated with $p_1$ would be more surprising than the event associated with $p_2$ and thus, $p_1 < p_2 \implies I(p_1) > I(p_2)$

- The surprise of a maximally probable event is zero. If an event has probability 1, then the event is certain to occur and we aren’t surprised at all of its occurance. Thus, \(I(1) = 0\)

- Surprise is additive. The suprise elicited from two independent events should be the sum of the two surprises. Intuitively, if one event occurs, it should not affect the surprise from the other event occuring because, after all, the two events are statistically independent. Thus, given two independent events with probabilities $p_1$ and $p_2$, it should follow that $I(p_1p_2) = I(p_1) + I(p_2)$. Generalizing to $n$ events: \(I\left(\prod_{i=1}^n p_i\right) = \sum_{i=1}^n I(p_i)\)

The self-information function

It turns out that the five properties outlined above can only be satisfied by one function! This function is simply:

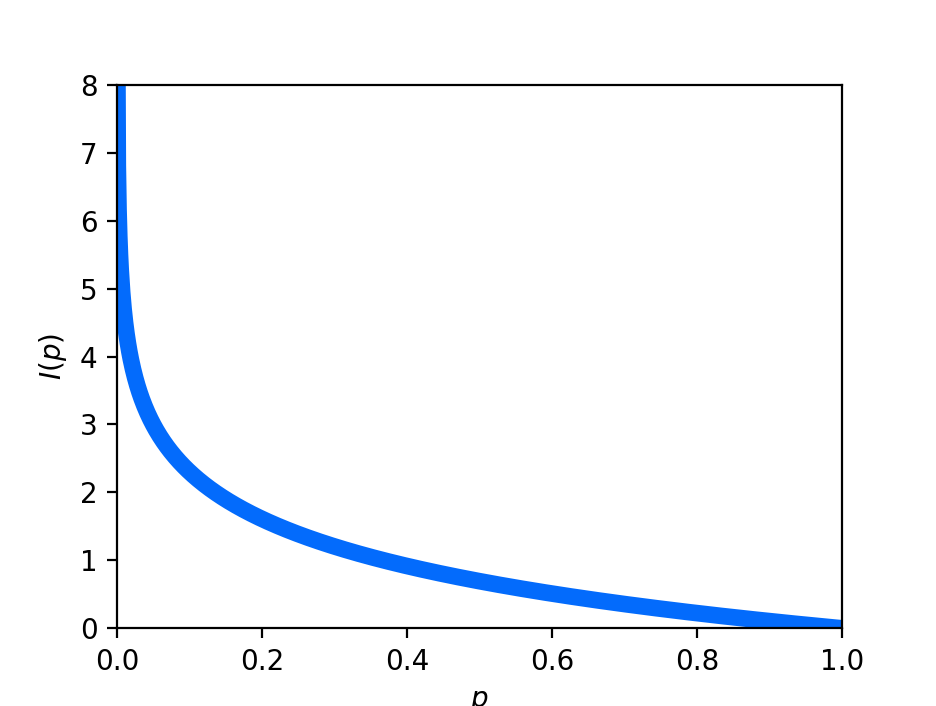

\[I(p) := -\log p\]This function looks like this:

Note that the base of the logarithm will alter the value of the self-information. As we will discuss in the next post, there is an alternative angle from which one can view the concept of information within information theory: as how efficiently one can communicate the occurance of the event. As we’ll see, the base of the logarithm of the self-information function can be understood to be the number of symbols we are utilizing to communicate the occurance of the event.