Span and linear independence

Published:

A very important concept linear algebra is that of linear independence. In this blog post we present the definition for the span of a set of vectors. Then, we use this definition to discuss the definition for linear independence. Finally, we discuss some intuition into this fundamental idea.

Introduction

A very important concept in the study of vector spaces is that of linear independence. At a high level, a set of vectors are said to be linearly independent if you cannot form any vector in the set using any combination of the other vectors in the set. If a set of vectors does not have this quality – that is, a vector in the set can be formed from some combination of others – then the set is said to be linearly dependent.

In this post, we will first present a more fundamental concept, the span of a set of vectors, and then move on to the definition for linear independence. Finally, we will discuss high-level intuition for why the concept of linear independence is so important.

Span

Given a set of vectors, the span of these vectors is the set of the vectors that can be “generated” by taking linear combinations of these vectors. More rigorously,

Definition 1 (span): Given a vector space, $(\mathcal{V}, \mathcal{F})$ and a set of vectors $S := \{ \boldsymbol{x}_1, \boldsymbol{x}_2, \dots, \boldsymbol{x}_n \} \in \mathcal{V}$, the span of $S$, denoted $\text{Span}(S)$ is the set of all vectors that can be formed by taking a linear combination of vectors in $S$. That is,

Intuitively, you can think of $S$ as a set of “building blocks” and the $\text{Span}(S)$ as the set of all vectors that can be “constructed” from these building blocks. To illustrate this point, we illustrate two vectors, $\boldsymbol{x}_1$ and $\boldsymbol{x}_2$ (left), and two examples of vectors in their span (right):

In this example we see that we can construct ANY two dimensional vector from $\boldsymbol{x}_1$ and $\boldsymbol{x_2}$. Thus, the span of these two vectors is all of $\mathbb{R}^2$! This is not always the case. In the figure below, we show an example of two vectors in $\mathbb{R}^2$ with a different span:

Here, $\boldsymbol{x}_1$ and $\boldsymbol{x_2}$ don’t span all of $\mathbb{R}^2$, but rather, only the line on which $\boldsymbol{x}_1$ and $\boldsymbol{x_2}$ lie.

Linear dependence and independence

Given a vector space, $(\mathcal{V}, \mathcal{F})$, and a set of vectors $S := \{ \boldsymbol{x}_1, \boldsymbol{x}_2, \dots, \boldsymbol{x}_n \} \in \mathcal{V}$, the vectors are said to be linearly independent if each vector lies outside the span of the remaining vectors. Otherwise, the vectors are said to be linearly dependent. More rigorously,

Definition 2 (linear independence): Given a vector space, $(\mathcal{V}, \mathcal{F})$ and a set of vectors $S := \{ \boldsymbol{x}_1, \boldsymbol{x}_2, \dots, \boldsymbol{x}_n \} \in \mathcal{V}$, $S$ is called linearly independent if for each vector $\boldsymbol{x_i} \in S$, it holds that $\boldsymbol{x}_i \notin \text{Span}(S \setminus \{ \boldsymbol{x}_i \})$.

Definition 2 (linear dependence): Given a vector space, $(\mathcal{V}, \mathcal{F})$ and a set of vectors $S := \{ \boldsymbol{x}_1, \boldsymbol{x}_2, \dots, \boldsymbol{x}_n \} \in \mathcal{V}$, $S$ is called linearly dependent if there exists a vector $\boldsymbol{x_i} \in S$, such that $\boldsymbol{x}_i \in \text{Span}(S \setminus \{ \boldsymbol{x}_i \})$.

Said differently, a set of vectors are linearly independent if you cannot form any of the vectors in the set using a linear combination of any of the other vectors. Below we demonstrate a set of linearly independent vectors (left) and a set of linearly dependent vectors (right):

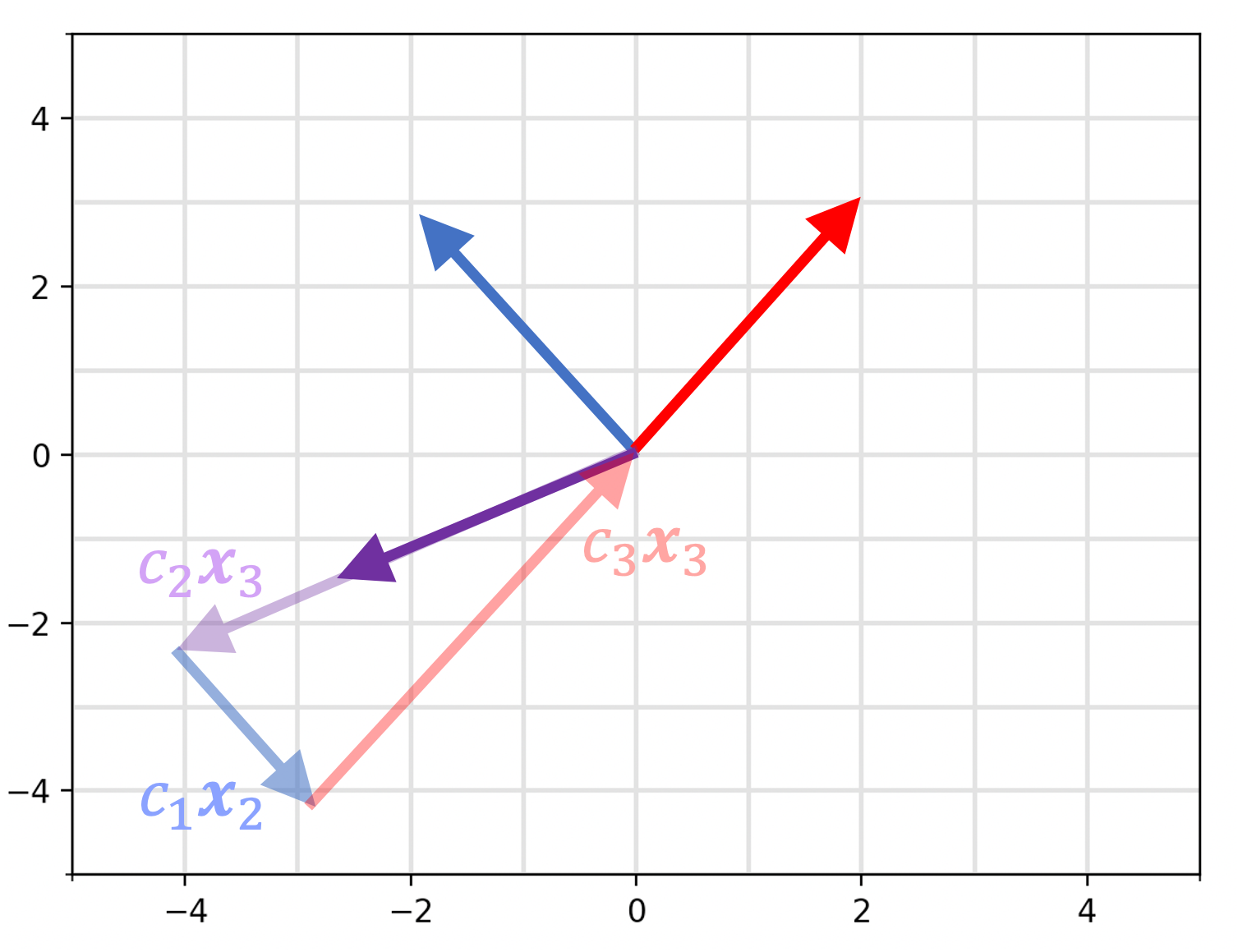

Why is the set on the right linearly dependent? As you can see below, we can use any of the two vectors to construct the third:

Linear dependence/independence among a set of vectors implies another key property about these vectors stated in the following theorems (proven in the Appendix to this post):

Theorem 1 (forming the zero vector from linearly dependent vectors): Given a vector space, $(\mathcal{V}, \mathcal{F})$ and a set of vectors $S := \{ \boldsymbol{x}_1, \boldsymbol{x}_2, \dots, \boldsymbol{x}_n \} \in \mathcal{V}$, $S$ is linearly dependent if and only if there exists a set of coefficients $c_1, \dots c_n$ for which $\sum_{i=1}^n c_i\boldsymbol{x}_i = \boldsymbol{0}$ and at least one coefficient is non-zero.

Corollary: $S$ is linearly independent if and only if the only assignment of values to coefficients $c_1, \dots c_n$ for which $\sum_{i=1}^n c_i\boldsymbol{x}_i = \boldsymbol{0}$ is the assignment for which all $c_1, \dots c_n$ are zero.

These theorems essentially says that if a set of vectors are linearly dependent, then one can construct the zero vector using a linear combination of the remaining vectors that isn’t the “trivial” linear combination of setting all of the coefficients to zero. This is illustrated below:

In contrast, Theorem 2 says that the only way to construct the zero vector from a set of linearly independent vectors is by setting all of the coefficients to zero.

Intuition for linear independence

There are two ways I think about linear independence: in terms of information content and in terms of intrinsic dimensionality. Let me explain.

First, if a set of vectors is linearly dependent, then in a sense there is “reduntant information” within these vectors. What do I mean by “redundant information”? In a linear dependent set, there exists a vector in that set for which if we removed that vector, the span of the set would remain the same! On the other hand, for a linearly independent set of vectors, each vector is vital for defining the span of the set’s vectors. If you remove even one vector, the span of the vectors will change (it will become smaller)!

One can also think about the concept of linear dependence/indepence in terms of intrinsic dimensionality . That is, a set of $n$ linearly independent vectors $S := \{ \boldsymbol{x}_1, \dots, \boldsymbol{x}_n \}$ spans a space with an intrinsic dimensionality of $n$ because in order to specify any vector $\boldsymbol{v}$ in the span of these vectors, one must specify the coefficients $c_1, \dots, c_n$ to construct $\boldsymbol{v}$ from the vectors in $S$. That is,

\[\boldsymbol{v} = c_1\boldsymbol{x}_1 + \dots + c_n\boldsymbol{x}_n\]However, if $S$ is linearly dependent, then we can throw away “redundant” vectors in $S$. In fact, we see that the intrinsic dimensionality of a linearly dependent set $S$ is the maximum sized subset of $S$ that is linearly independent!

Appendix

Theorem 1 (forming the zero vector from linearly dependent vectors): Given a vector space, $(\mathcal{V}, \mathcal{F})$ and a set of vectors $S := \{ \boldsymbol{x}_1, \boldsymbol{x}_2, \dots, \boldsymbol{x}_n \} \in \mathcal{V}$, $S$ is linearly dependent if and only if there exists an assignment of values to coefficients $c_1, \dots c_n$ for which $\sum_{i=1}^n c_i\boldsymbol{x}_i = \boldsymbol{0}$ and at least one coefficient is non-zero.

Proof:

We must prove both directions of the “if and only if”. Let’s start by proving that if there exists an assignment of coefficients that are not all zero for which $\sum_{i=1}^n c_i\boldsymbol{x}_i = \boldsymbol{0}$, then $S$ is linearly dependent.

Let’s assume that we have a set of coefficients $c_1, \dots c_n$ such that

\[\sum_{i=1}^n c_i\boldsymbol{x}_i = \boldsymbol{0}\]and that not all of the coefficients are zero and let $C$ be the set of indices of the coefficients that are not zero. Then, we can write

\[\sum_{i \in C} c_i\boldsymbol{x}_i = \boldsymbol{0}\]There are now two scenarios to consider: $C$ is of size 1 and $C$ is of size greater than 1. Let’s first assume $C$ is of size 1 and let’s let $k$ be the index of the one and only coefficient that is non-zero. Then

\[c_k\boldsymbol{x}_k = \boldsymbol{0}\]We see that $\boldsymbol{x}_k$ must be the zero vector (because $c_k$ is nonzero). This implies that the zero vector is in $S$. The zero vector is in the span of the remaining vectors in $S$ (since we can form a linear combination of the remaining vectors to form $S$ by simply setting their coefficients to zero). This implies that $S$ is linearly dependent.

Let’s assume that $C$ is of size greater than one. Then for any $k \in C$, we can write:

\[\begin{align*} \sum_{i \in C \setminus \{ k \} } c_i \boldsymbol{x}_i &= - c_k \boldsymbol{x}_k \\ \implies -\frac{1}{c_k} \sum_{i \in C \setminus \{ k \} } c_i\boldsymbol{x}_i &= \boldsymbol{x}_k \\ \implies \sum_{i \in C \setminus \{ k \}} -\frac{c_i}{c_k} \boldsymbol{x}_i &= \boldsymbol{x}_k \end{align*}\]Thus we see that $\boldsymbol{x}_k$ is in the span of the remaining vectors and thus $S$ is linearly dependent.

Now we will prove the other direction of the “if and only if”: if $S$ is linearly dependent then there exists an assignment of coefficients that are not all zero for which $\sum_{i=1}^n c_i\boldsymbol{x}_i = \boldsymbol{0}$.

If $S$ is linearly dependent then there exists a vector $\boldsymbol{x}_n \in S$ that we can form using a linear combination of the remaining vectors in $S$. Let $\boldsymbol{x}_1, \dots \boldsymbol{x}_{n-1}$ be these remaining vectors. There are now two scenarios to consider: $\boldsymbol{x}_n$ is the zero vector or $\boldsymbol{x}_n$ is not the zero vector.

If $\boldsymbol{x}_n$ is the zero vector, then we see that we can assign zero to the coefficients $c_1, \dots, c_{n-1}$ and any non-zero value to $c_n$ and the following will hold:

\[c_n \boldsymbol{x}_n + \sum_{i=1}^{n-1} c_i \boldsymbol{x}_i = \boldsymbol{0}\]Thus there exists an assignment of coefficients that are not all zero for which $\sum_{i=1}^n c_i\boldsymbol{x}_i = \boldsymbol{0}$.

Now let’s say that $\boldsymbol{x}_n$ is not the zero vector. Then,

\[\sum_{i=1}^{n-1} c_i \boldsymbol{x}_i = \boldsymbol{x}_n \implies \left(\sum_{i=1}^{n-1} c_i \boldsymbol{x}_i\right) - \boldsymbol{x}_n = \boldsymbol{0}\]Here, the cofficient for $\boldsymbol{x}_n$ is -1, which is non-zero. Thus there exists an assignment of coefficients that are not all zero for which $\sum_{i=1}^n c_i\boldsymbol{x}_i = \boldsymbol{0}$.

$\square$