Intrinsic dimensionality

Published:

In my formal education, I found that the concept of “intrinsic dimensionality” was never explicitly taught; however, it undergirds so many concepts in linear algebra and the data sciences such as the rank of a matrix and feature selection. In this post I will discuss the difference between the extrinsic dimensionality of a space versus its intrinsic dimensionality.

Introduction

An important concept in linear algebra and the data sciences is the idea of intrinsic dimensionality. I found that in my formal education this concept was never explicitly taught; however, it undergirds so many concepts in linear algebra and data analysis. In this post I will discuss the difference between the extrinsic dimensionality of a space versus its intrinsic dimensionality. These general ideas provides a nice framework for understanding such diverse concepts as the rank of a matrix in linear algebra as well as dimension reduction and feature selection in machine learning.

What exactly is a “space”?

Before jumping into the dimensionality of spaces, let’s first address a very basic question: what is a space? According to Wikipedia, a space is a set of objects with some “structure.” This definition is extremely general, perhaps even trivial, but I think it deserves emphasizing that a space is, first and foremost, a set. When we refer to “three-dimensional space”, we are in essence describing the set of all points in three dimensions. As I’ve said, this may seem trivial at first, but I think it will be an important idea as we move on to describe the concept of “intrinsic dimensionality.”

What is a dimension?

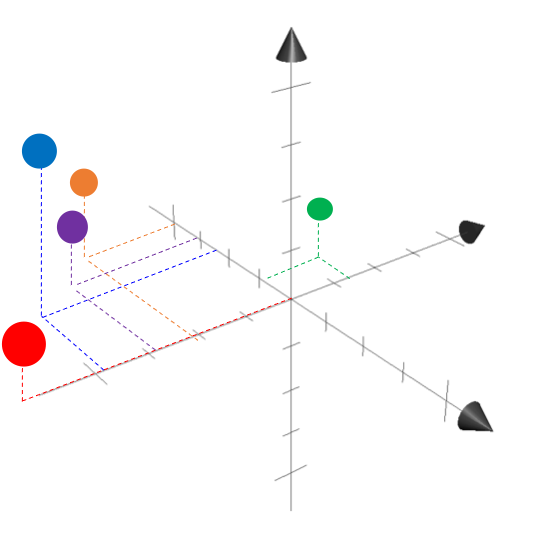

Let’s move on to another basic question: what does it mean for a space to be three-dimensional versus two-dimensional? More generally, what does it mean for a space to be $D$-dimensional? A basic answer to this question is that a $D$-dimensional space is one in which $D$ pieces of information (i.e., characteristics) are required to describe each object in that space. These $D$ pieces of information are called dimensions. For example, in three-dimensional Euclidean space (3D space), we need three pieces of information to describe each point: its value along the x-axis, its value along the y-axis, and its value along the z-axis:

Intrinsic vs. extrinsic dimensionality

Now that we have some basic ideas down – namely, “space” and “dimensions” – let’s move on to the core of this blog post: intrinsic dimensionality. Before we move on, let me spoil the ending: the intrinsic dimensionality of a space is the number of required pieces of information that we need to describe each object in the space. This may differ from the number of pieces of information that we are using, which we call the extrinsic dimensionality of the space.

Let’s make this concrete with an example. Let’s say we’re in some situtation we’re we are dealing with objects in some extrinsically $D$-dimensional space. Thus, we are dealing with $D$ pieces of information for describing objects in that space. One may ask a simple question: do we really need $D$ pieces of information to describe each object? Or can we get by with fewer?

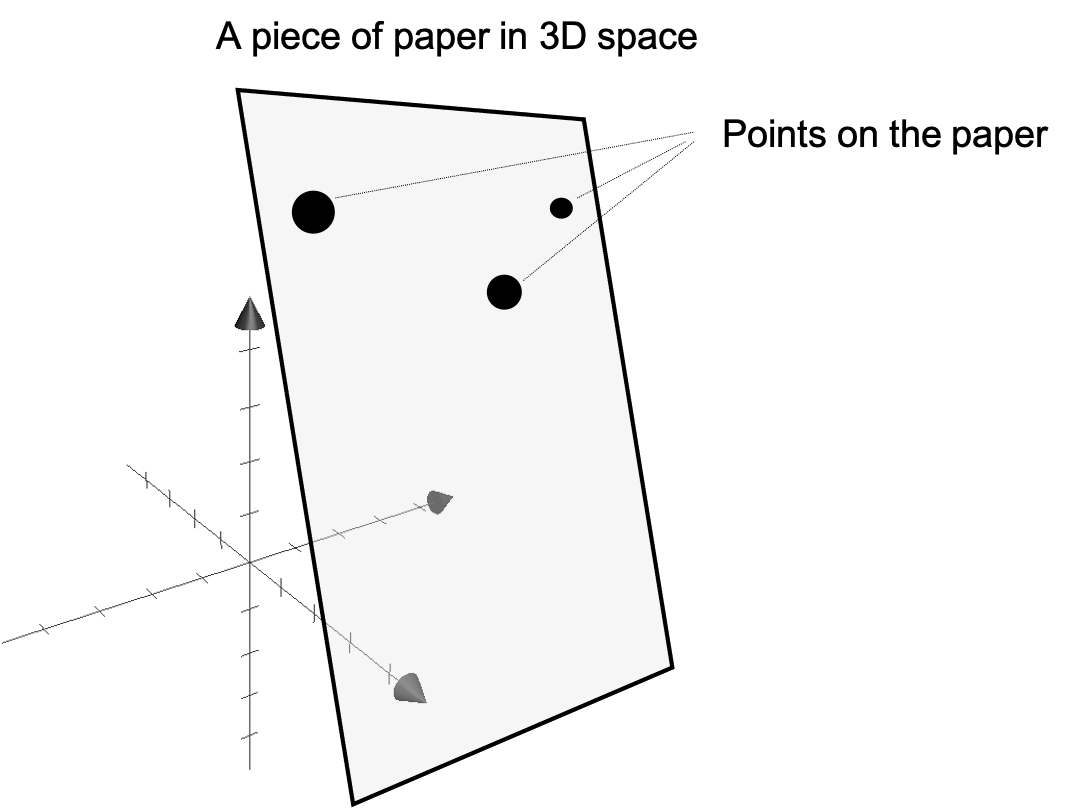

Take the following example: we want to describe all points on a flat piece of paper in 3D space. That is, all of the points that we care about will lie only on the sheet of paper.

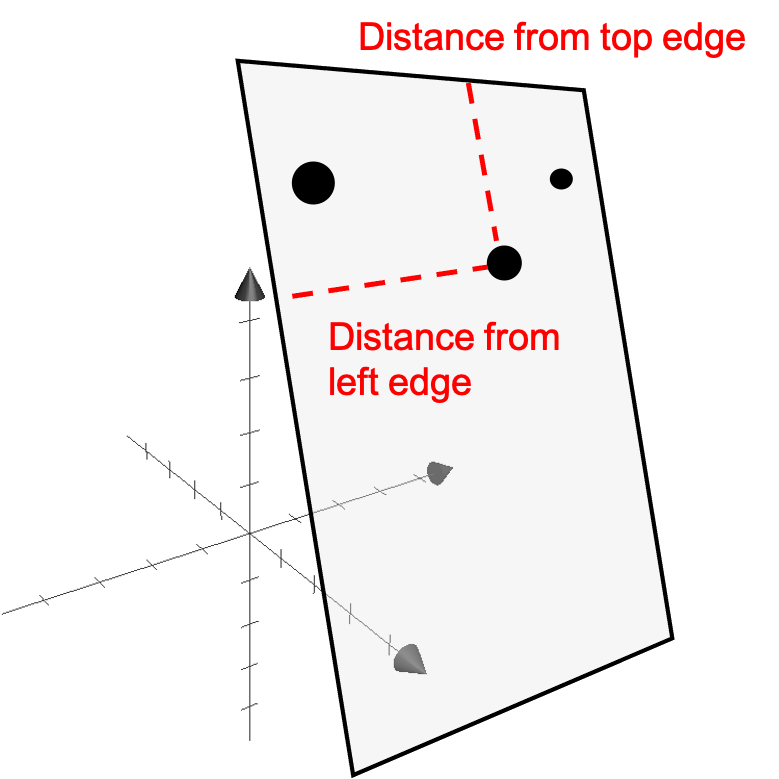

Of course, we can use each points x, y, and z coordinates, but do we really need three pieces of information to describe each point on the paper? The answer is no, we really only need two! Intuitively, we can specify each point on the paper using two coordinates: its distance from the left edge of the paper and its distance from the top edge of the paper:

Of course, representing each point on the paper using these new coordinates requires keeping track of the position of the left edge and top edge in 3D space; however, once we have this information handy, then every point on the paper can be represented using only these two coordinates.

The intrinsic dimensionality of a space is the number of required pieces of information for representing each object. In the piece of paper example, only two coordinates are needed to describe each point on the paper, and thus, it can be said that the “space” of the paper (i.e., the set of all points that lie on the paper) is intrinsically only two-dimensional rather than three-dimensional. Notably, the intrinsic dimensionality of a space may be different than its explicit dimensionality. That is, even though we may be representing each point on the paper using their original three coordinates in 3D space, we could instead only use two.

When will the intrinsic dimensionality of a space be smaller than its extrinsic dimensionality? Intuitively, this will happen when the space that we care about can be formed by taking a subset of the full extrinsic space. In the piece of paper example of above, we only care about the subset of points in 3D space that lie on the piece of paper. By taking a subset, we are in essence coming up with a new, smaller space than the full 3D space. Such spaces are called subspaces.

Another example

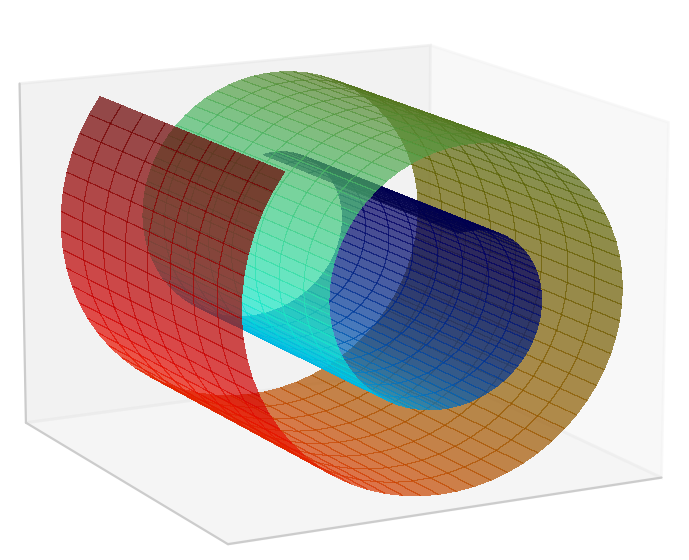

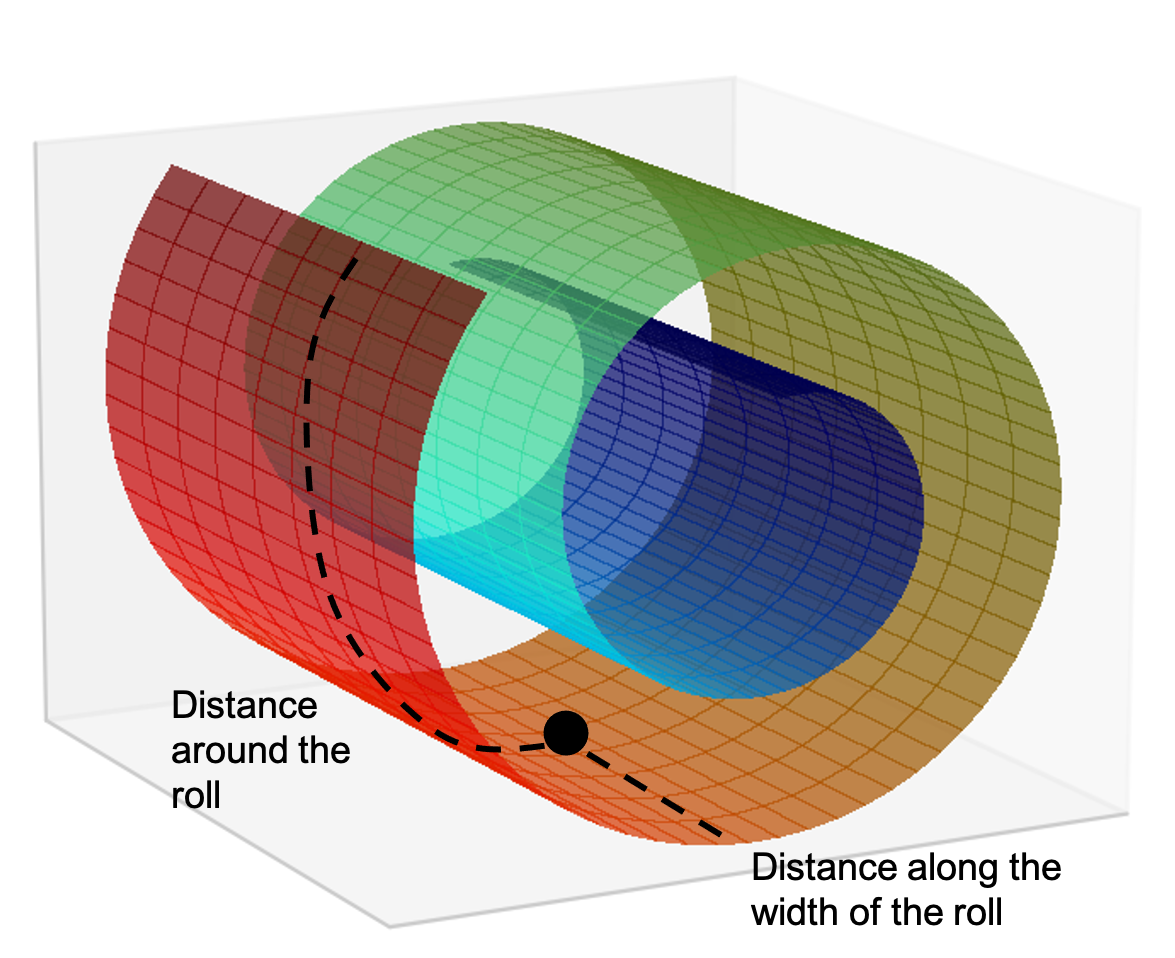

Here’s another example of a piece of paper embedded in 3D space, but this time, the paper is rolled up in a “Swiss roll” shape:

Again, one may say that the set of points that lie on the Swiss roll forms an intrinsically two dimensional space rather than a 3D space. The reason is that we can represent each point using two pieces of information: its distance along the width of the roll and its distance around the roll:

This is very high level and we haven’t described a rigorous system of coordinates for actually describing each point on the roll, but intuitively one can see that if one fixed the geometry of the roll, one could easily describe each point on the roll with only two dimensions.