Normed vector spaces

Published:

When first introduced to Euclidean vectors, one is taught that the length of the vector’s arrow is called the norm of the vector. In this post, we present the more rigorous and abstract definition of a norm and show how it generalizes the notion of “length” to non-Euclidean vector spaces. We also discuss how the norm induces a metric function on pairs of vectors so that one can discuss distances between vectors.

Introduction

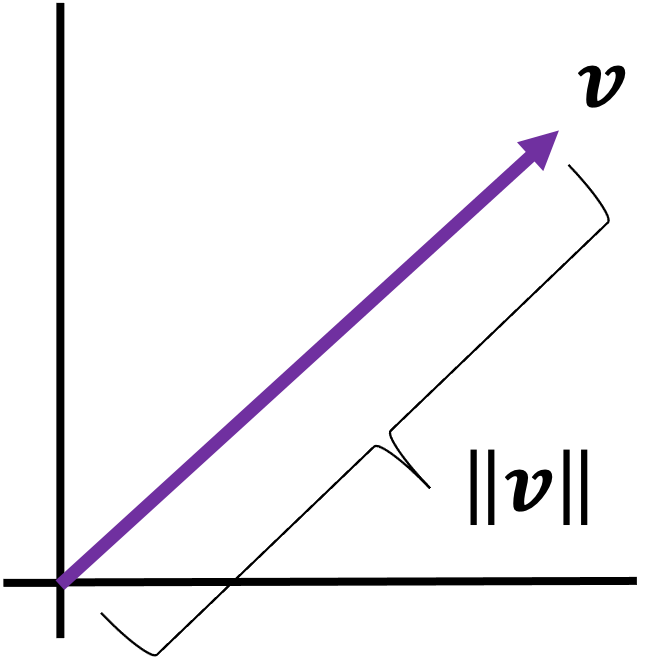

A normed vector space is a vector space in which each vector is associated with a scalar value called a norm. In a standard Euclidean vector spaces, the length of each vector is a norm:

The more abstract, rigorous definition of a norm generalizes this notion of length to any vector space as follows:

Definition 1 (normed vector space): A normed vector space is vector space $(\mathcal{V}, \mathcal{F})$ associated with a function $||.|| : \mathcal{V} \rightarrow \mathbb{R}$, called a norm, that obeys the following axioms:

- $\forall \boldsymbol{v} \in \mathcal{V}, \ \ ||\boldsymbol{v}|| \geq 0$

- $\forall \boldsymbol{v} \in \mathcal{V}, \forall \alpha \in \mathcal{F}, \ \ ||\alpha\boldsymbol{v}|| = |\alpha| ||\boldsymbol{v}||$

- $\forall \boldsymbol{v}, \boldsymbol{u} \in \mathcal{V}, \ \ ||\boldsymbol{u} + \boldsymbol{v}|| \leq ||\boldsymbol{u}|| + ||\boldsymbol{v}||$

Here, we outline the intuition behind each axiom in the definition above and describe how these axioms capture this idea of length:

- Axiom 1 says that all vectors should have a positive length. This enforces our intuition that a “length’’ is a positive quantity.

- Axiom 2 says that if we multiply a vector by a scalar, it’s length should increase by the magnitude (i.e. the absolute value) of that scalar. This axiom ties together the notion of scaling vectors (Axiom 6 in the definition of a vector space) to the notion of “length” for a vector. It essentially says that to scale a vector is to stretch the vector.

- Axiom 3 says that the length of the sum of two vectors should not exceed the sum of the lengths of each vector. This enforces our intuition that if we add together two objects that each have a “length”, the resultant object should not exceed the sum of the lengths of the original objects.

Following the axioms for a normed vector space, one can also show that only the zero vector has zero length (Theorem 1 in the Appendix to this post).

Unit vectors

In a normed vector space, a unit vector is a vector with norm equal to one. Given a vector $\boldsymbol{v}$, a unit vector can be derived by simply dividing the vector by its norm (Theorem 2 in the Appendix). This unit vector, called the normalized vector of $\boldsymbol{v}$ is denoted $\hat{\boldsymbol{v}}$. In a Euclidean vector space, the normalized vector $\hat{\boldsymbol{v}}$ is the unit vector that points in the same direction as $\boldsymbol{v}$.

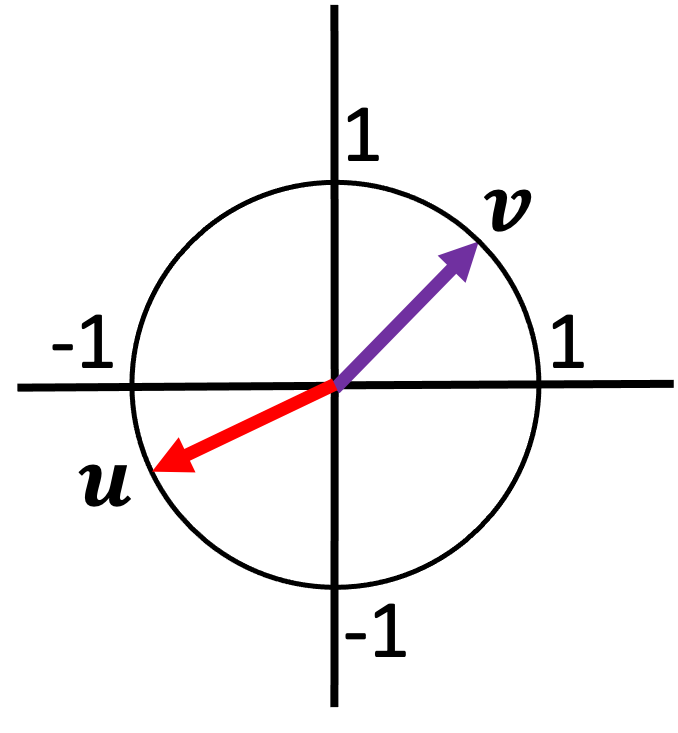

Unit vectors are important because they generalize the idea of “direction” in Euclidean spaces to vector spaces that are not Euclidean. In a Euclidean space, the unit vectors all fall in a sphere of radius one around the origin:

Thus, the set of all unit vectors can be used to define the set of all “directions” that vectors can point in the vector space. Because of this, one can form any vector by decomposing it into a unit vector multiplied by some scalar. In this way, unit vectors generalize the notion of “direction” in a Euclidean vector space to non-Euclidean vector spaces.

Normed vector spaces are also metric spaces

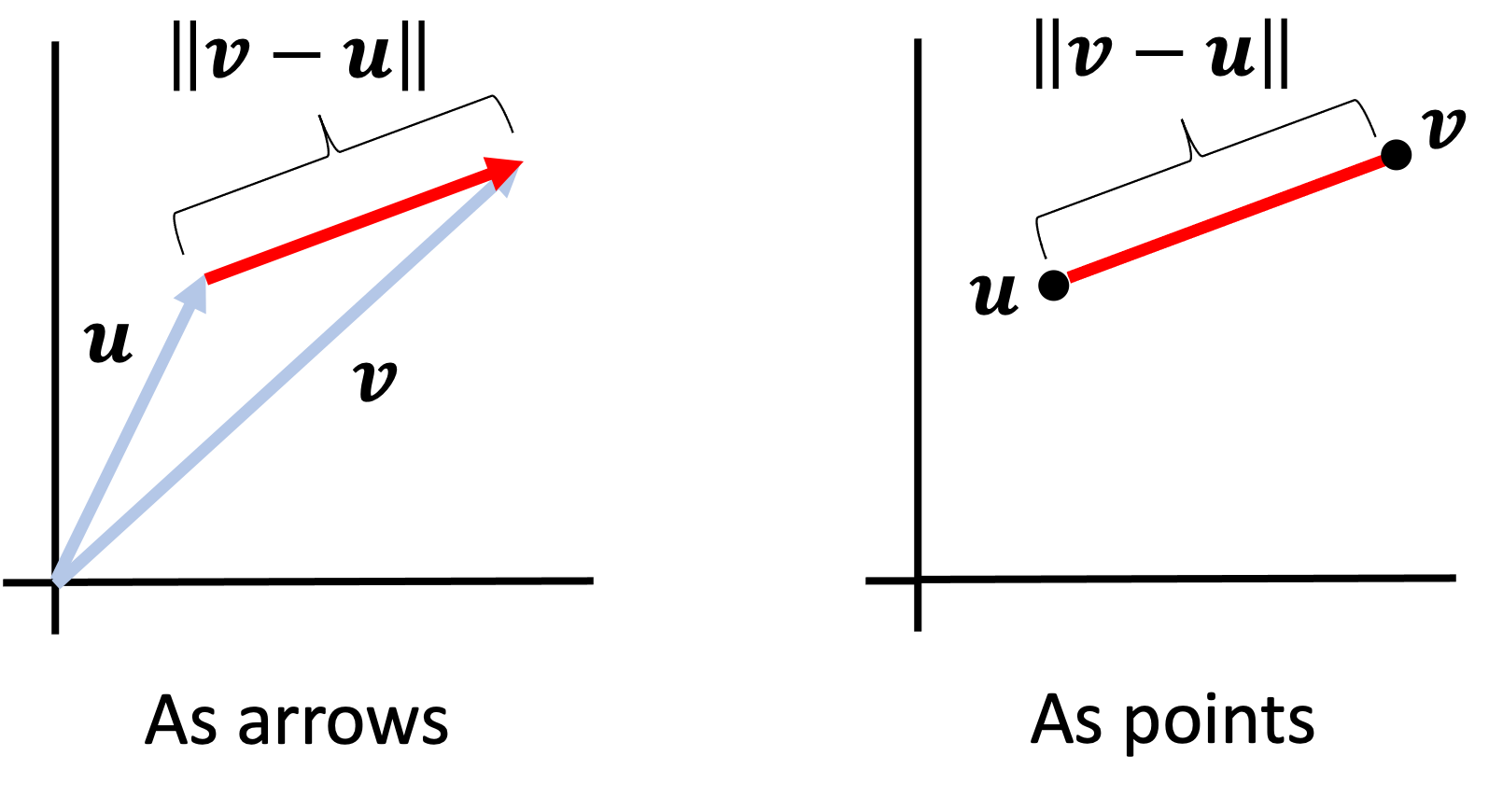

All normed vector spaces are also metric spaces – that is, the norm function induces a metric function on pairs of vectors that can be interpreted as a “distance” between them (Theorem 3 in the Appendix). This metric is defined simply as:

\[d(\boldsymbol{x}, \boldsymbol{y}) := \|\boldsymbol{x} - \boldsymbol{y}\|\]That is, if one subtracts one vector from the other, then the “length” of the resultant vector can be interpreted as the “distance” between those vectors.

In the figure below we show how the norm can be used to form a metric between Euclidean vectors. On the left, we depict two vectors, $\boldsymbol{v}$ and $\boldsymbol{u}$, as arrows. On the right we depict these vectors as points in Euclidean space. The distance between these points is given by the norm of the difference vector between $\boldsymbol{u}$ and $\boldsymbol{v}$.

Examples of norms

Notably, a norm is a function that satisfies a set of axioms and thus, one may consider multiple norms when looking at a vector space. For example, there are multiple norms that are commonly associated with Euclidean vector spaces. Here are just a few examples:

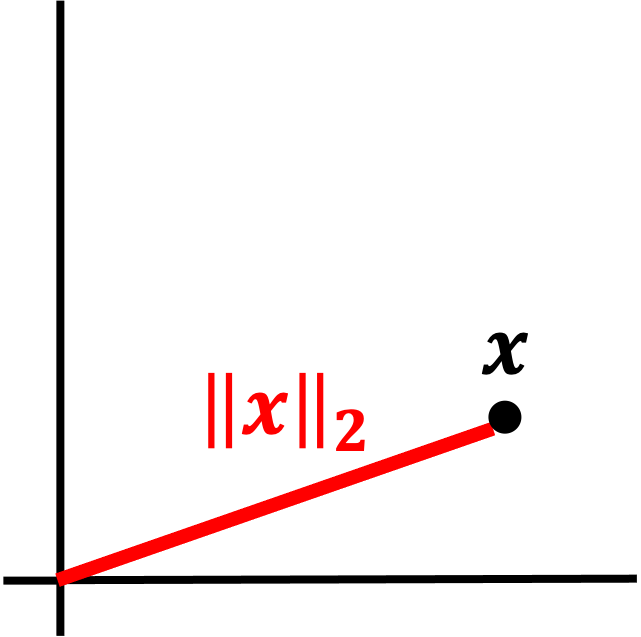

L2 norm

The L2 norm is the most common norm as it is simply the Euclidean distance between points in a coordinate vector space:

\[\vert\vert \boldsymbol{x} \vert\vert_2 := \sqrt{\sum_{i=1}^n x_i^2}\]

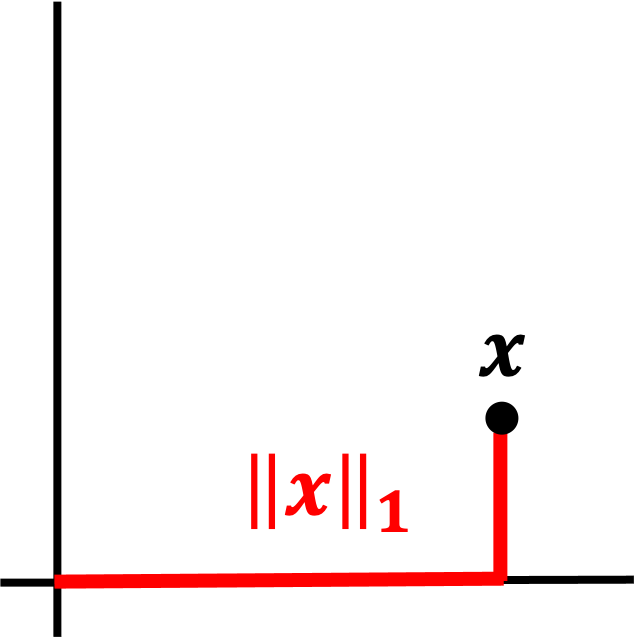

L1 norm

The L1 norm is simply a sum of the of the absolute values of the elements of the vector:

\[\vert\vert \boldsymbol{x} \vert\vert_1 := \sum_{i=1}^n \vert x_i \vert\]The L1 norm is also alled the Manhattan norm or taxicab norm because it calculates distances as if one has to take streets around city blocks to get from one point to another:

Infinity norm

The infinity norm is simply the maximum value among the elements of a vector:

\[\vert\vert \boldsymbol{x} \vert\vert_{\infty} := \text{max}\{x_1, x_2, \dots, x_n\}\]

Appendix

Theorem 1 (Only the zero vector has zero norm): Given a vector space $(\mathcal{V}, \mathcal{F})$ with norm $\vert\vert . \vert\vert$, it holds that $\vert\vert \boldsymbol{v} \vert\vert = 0 \iff \boldsymbol{v} = \boldsymbol{0}$

Proof:

\[\begin{align*}\vert\vert \boldsymbol{0} \vert\vert &= \vert\vert 0 \boldsymbol{v} \vert\vert && \text{for any $\boldsymbol{v} \in \mathcal{V}$} \\ &= \vert 0 \vert \vert\vert \boldsymbol{v} \vert\vert && \text{by Axiom 2} \\ &= 0\end{align*}\]Note the first line is proven in Theorem 2 in my previous blog post on vector spaces.

$\square$

Theorem 2 (Formation of unit vector): Given a vector space $(\mathcal{V}, \mathcal{F})$ with norm $\vert\vert . \vert\vert$, the vector $\hat{\boldsymbol{v}} := \frac{\boldsymbol{v}}{\vert\vert \boldsymbol{v} \vert\vert}$ has norm equal to one.

Proof:

\[\begin{align*}\vert\vert \hat{\boldsymbol{v}} \vert\vert &= \vert\vert \frac{\boldsymbol{v}}{\vert\vert \boldsymbol{v} \vert\vert} \vert\vert \\ &=\frac{1}{\vert\vert\boldsymbol{v}\vert\vert} \vert\vert\boldsymbol{v}\vert\vert \\ &= 1 \end{align*}\]$\square$

Theorem 3 (Norm-induced metric): Given a vector space $(\mathcal{V}, \mathcal{F})$ with norm $\vert\vert . \vert\vert$, the function $d(\boldsymbol{x}, \boldsymbol{y}) := \vert\vert \boldsymbol{x} - \boldsymbol{y} \vert\vert$ where $\boldsymbol{x}, \boldsymbol{y} \in \mathcal{V}$ is is a metric.

Proof:

To prove that $d$ is a metric, we need to show that it satisfies the three axioms of a metric function. First we need to show that

\[d(\boldsymbol{x}, \boldsymbol{y}) = 0 \iff \boldsymbol{x} = \boldsymbol{y}\]This can be proven as follows:

\[\begin{align*} d(\boldsymbol{x}, \boldsymbol{y}) = 0 \implies & \vert\vert\boldsymbol{x} - \boldsymbol{y} \vert\vert = 0 \\ \implies & \vert\vert \boldsymbol{x} + (-\boldsymbol{y})\vert\vert = 0 \\ \implies & \boldsymbol{x} + (-\boldsymbol{y}) = \boldsymbol{0} && \text{by Theorem 1} \\ \implies & \boldsymbol{y} = -1 \boldsymbol{x} \\ \implies & \boldsymbol{y} = \boldsymbol{x}\end{align*}\]The last line follows from Theorem 4 in my previous blog post on vector spaces. Going the other direction, we assume that \(\boldsymbol{x} = \boldsymbol{y}\). Then

\[\begin{align*} \vert\vert \boldsymbol{y} - \boldsymbol{x} \vert\vert &= \vert\vert \boldsymbol{x} - \boldsymbol{x} \vert\vert \\ &= \vert\vert \boldsymbol{0} \vert\vert \\ &= 0 && \text{by Theorem 1}\end{align*}\]Second, we need to show that $d(\boldsymbol{x}, \boldsymbol{y}) \geq 0$. This fact is already evident based on Axiom 1 in Definition 1 above.

Third and finally, $d$ needs to satisfy the triangle inequality. That is, we need to show that $\forall \boldsymbol{x}, \boldsymbol{y}, \boldsymbol{z} \in \mathcal{V}$, it holds that

\[d(\boldsymbol{x}, \boldsymbol{y}) \leq d(\boldsymbol{x}, \boldsymbol{z}) + d(\boldsymbol{z}, \boldsymbol{y})\]This is proven as follows:

\[\begin{align*} d(\boldsymbol{x}, \boldsymbol{y}) &= \vert\vert\boldsymbol{x} - \boldsymbol{y} \vert\vert \\ &= \vert\vert\boldsymbol{x} - \boldsymbol{z} + \boldsymbol{z} - \boldsymbol{y} \vert\vert \\ &= \vert\vert(\boldsymbol{x} - \boldsymbol{z}) + (\boldsymbol{z} - \boldsymbol{y}) \vert\vert \\ & \leq \vert\vert\boldsymbol{x} - \boldsymbol{z}\vert\vert\ + \vert\vert\ \boldsymbol{z} - \boldsymbol{y} \vert\vert && \text{by Axiom 3 of Definition 1} \\ &= d(\boldsymbol{x}, \boldsymbol{z}) + d(\boldsymbol{z}, \boldsymbol{y})\end{align*}\]$\square$