Denoising diffusion probabilistic models (Part 2: Theoretical justification)

Published:

In Part 1 of this series, we introduced the denoising diffusion probabilistic model for modeling and sampling from complex distributions. We described the diffusion model as a model that can generate new samples by learning how to reverse a diffusion process. In this post, we provide more theoretical justification for the objective function used to fit diffusion models and make connections between the diffusion model and other concepts in statistical inference and probabilistic modeling.

Introduction

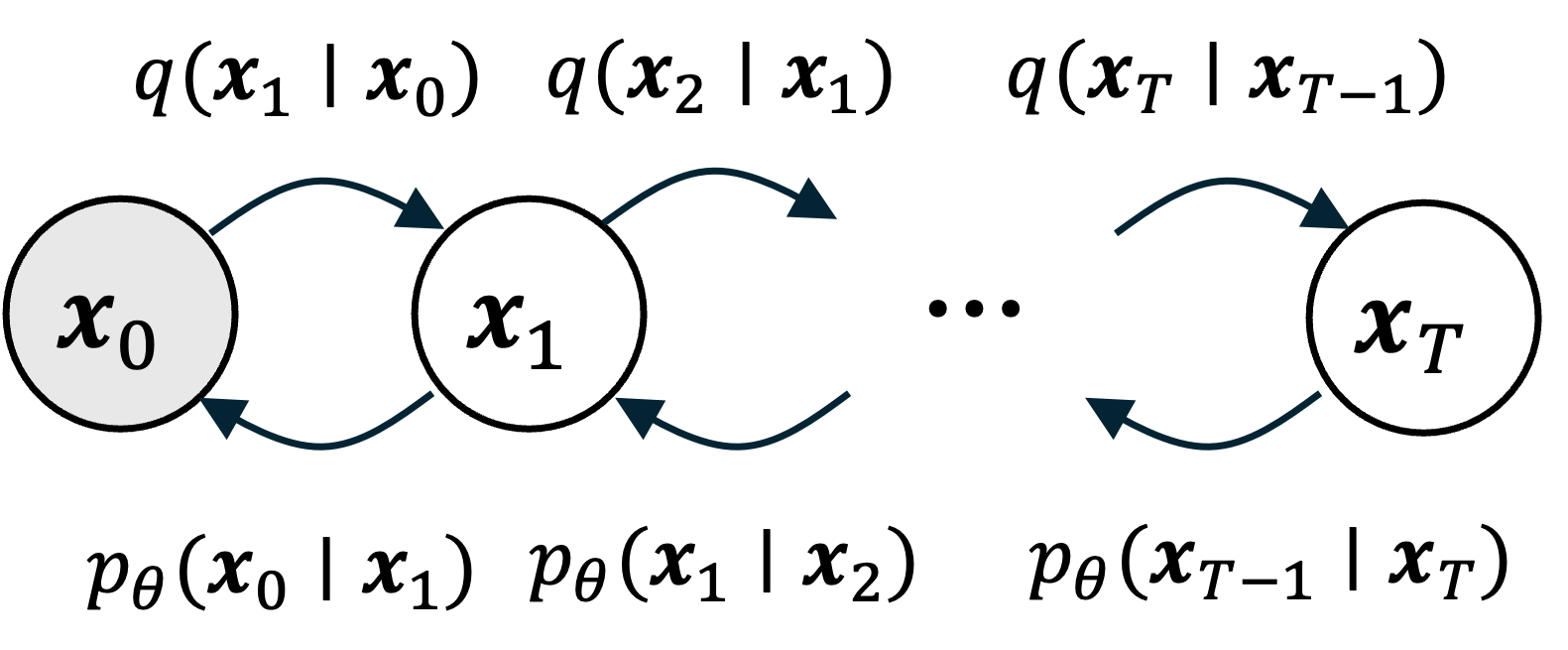

In Part 1 of this series, we introduced the denoising diffusion probabilistic model for modeling and sampling from complex distributions. As a brief review, diffusion models learn how to reverse a diffusion process. Specifically, given a data object $\boldsymbol{x}$, this diffusion process iteratively adds noise to $\boldsymbol{x}$ until it becomes pure white noise. The goal of a diffusion model is to learn to reverse this diffusion process via a model $p_\theta$ parameterized by parameters $\theta$:

Once we have this model in hand, we can generate an object by first sampling white noise $\boldsymbol{x}_T$ from a standard normal distribution $N(\boldsymbol{0}, \boldsymbol{I})$, and then iteratively sampling $\boldsymbol{x}_{t-1}$ from each learned $p_{\theta}(\boldsymbol{x}_{t-1} \mid \boldsymbol{x}_{t})$ distribution. At the end of this process we will have “transformed” the random white noise into an object.

To learn this model, we will fit the joint distribution given by the reverse-diffusion model, $p_{\theta}(\boldsymbol{x}_{0:T})$, to joint distribution given by the forward-diffusion model, $q(\boldsymbol{x}_{0:T})$. Specifically, we will seek to minimize the KL-divergence from $p_\theta(\boldsymbol{x}_{0:T})$ to $q(\boldsymbol{x}_{0:T})$:

\[\hat{\theta} := \text{arg min}_\theta \ KL( q(\boldsymbol{x}_{0:T}) \ \vert\vert \ p_\theta(\boldsymbol{x}_{0:T}))\]While the core idea of learning a denoising model that reverses a diffusion process and then using that denoising model to produce samples may be intuitive at a high-level, one may be wanting for a more rigorous theoretical motivation for the objective function that entails fitting $p_\theta(\boldsymbol{x}_{0:T})$ to $q(\boldsymbol{x}_{0:T})$ by minimizing their KL-divergence. That is, recall that the goal in traditional probabilistic modeling is fit a model $p_\theta(\boldsymbol{x}_0)$ that approximates the real-world, unknown distribution $q(\boldsymbol{x}_0)$. How does fitting a model to a reverse a diffusion lead accompish this task? Furthermore, what traditional statistical inference frameworks is this related to?

In this post we will answer these questions by discussing several perspectives to motivate and understand the diffusion model objective. Specifically, we will view this objective in the following ways:

- As maximum-likelihood estimation

- As implicitly minimizing an upper bound on the KL-divergence between $q(\boldsymbol{x}_0)$ and $p_\theta(\boldsymbol{x}_0)$

- As training a hierarchical variational autoencoder that uses a parameterless inference model

- As breaking up a difficult problem into many easier problems

A 5th perspective that motivates the loss function lies in its connection with score matching models; however, this merits a longer conversation that should be provided its own post. Stay tuned!

1. As maximum-likelihood estimation

Our reverse diffusion process can be thought about as a model, like any other, over noiseless objects $\boldsymbol{x}_0$, which we can access by marginalizing over all of the intermediate objects $\boldsymbol{x}_{1:T}$:

\[p_\theta(\boldsymbol{x}_0) = \int p(\boldsymbol{x}_0, \boldsymbol{x}_{1:T}) \ d\boldsymbol{x}_{1:T}\]It turns out that minimizing the KL-divergence from $p_\theta(\boldsymbol{x}_{0:T})$ to $q(\boldsymbol{x}_{0:T})$ can be viewed as doing approximate maximum likelihood esimation.

To see why, remember how we showed that minimizing the KL-divergence from $p_\theta(\boldsymbol{x}_{0:T})$ to $q(\boldsymbol{x}_{0:T})$ could be accomplished implicitly by maximizing the ELBO:

\[\begin{align*}\hat{\theta} &:= \text{arg max}_\theta \ \text{ELBO}(\theta) \\ &= \text{arg max}_\theta \ E_{\boldsymbol{x}_{1:T} \mid \boldsymbol{x}_0 \sim q}\left[ \log\frac{p_\theta (\boldsymbol{x}_{0:T}) }{q(\boldsymbol{x}_{1:T} \mid \boldsymbol{x}_0) } \right]\end{align*}\]Notice that if we maximize the ELBO, we are not only minimizing the KL-divergence (our original stated goal), but we are also implicitly maximizing a lower bound of the log-likelihood, $\log p_\theta(\boldsymbol{x})$. That is, we see that

\[\begin{align*} \log p_\theta(\boldsymbol{x}) &= KL( q(\boldsymbol{x}_{1:T} \mid \boldsymbol{x}_0) \ \vert\vert \ p_\theta(\boldsymbol{x}_{1:T} \mid \boldsymbol{x}_0)) + \underbrace{E_{\boldsymbol{x}_{1:T} \mid \boldsymbol{x}_0 \sim q} \left[ \log\frac{p_\theta (\boldsymbol{x}_{0:T}) }{q(\boldsymbol{x}_{1:T} \mid \boldsymbol{x}_0) } \right]}_{\text{ELBO}} \\ &\geq \underbrace{E_{\boldsymbol{x}_{1:T} \mid \boldsymbol{x}_0 \sim q}\left[ \log\frac{p_\theta (\boldsymbol{x}_{0:T}) }{q(\boldsymbol{x}_{1:T} \mid \boldsymbol{x}_0) } \right]}_{\text{ELBO}} \ \ \text{Because KL-divergence is non-negative} \end{align*}\]This idea is depicted schematically below (this figure is adapted from this blog post by Jakub Tomczak):

Here, $\theta^*$ represents the maximum likelihood estimate of $\theta$ and $\hat{\theta}$ represents the value for $\theta$ that maximizes the ELBO. If this lower-bound is tight, $\hat{\theta}$ will be close to $\hat{\theta}$. Although in most cases, it is difficult to know with certainty how tight this lower bound is, in practice, this strategy of maximizing the ELBO leads to good results at estimating $\theta^*$.

2. As implicitly minimizing an upper bound on the KL-divergence between $q(\boldsymbol{x}_0)$ and $p_\theta(\boldsymbol{x}_0)$

Recall that our ultimate goal in fitting a denoising diffusion model is to fit a model $p_\theta(\boldsymbol{x}_0)$ that approximates the real-world, unknown distribution $q(\boldsymbol{x}_0)$. As we described in the previous section, $p_\theta(\boldsymbol{x}_0)$ can be obtained by marginalizing over all of the intermediate objects $\boldsymbol{x}_{1:T}$.

As explained eloquently by Alexander Alemi in his blog post on this topic, by minimizing the KL-divergence between the full diffusion process’s joint distributions, $p_\theta(\boldsymbol{x}_{0:T})$ and $q(\boldsymbol{x}_{0:T})$, we will implicitly minimize an upper bound on the KL-divergence from $p_\theta(\boldsymbol{x}_0)$ to $q(\boldsymbol{x}_0)$ (See Derivation 1 in the Appendix to this post):

\[KL(q(\boldsymbol{x}_{0:T}) \ \vert\vert \ p_\theta(\boldsymbol{x}_{0:T})) \geq KL(q(\boldsymbol{x}_0) \ \vert\vert \ p_\theta(\boldsymbol{x}_0)) \geq 0\]Thus, by minimizing $KL(q(\boldsymbol{x}_{0:T}) \ \vert\vert \ p_\theta(\boldsymbol{x}_{0:T}) )$, we are implicitly learning to fit $p_\theta(\boldsymbol{x}_0)$ to $q(\boldsymbol{x}_0)$!

3. As training a hierarchical variational autoencoder that uses a parameterless inference model

In the last section, we showed that fitting $p_\theta(\boldsymbol{x}_{0:T})$ to $q(\boldsymbol{x}_{0:T})$ will implicitly minimize an upper bound on the KL-divergence from $p_\theta(\boldsymbol{x}_0)$ to $q(\boldsymbol{x}_0)$. This begs the question: Why don’t we fit $p_\theta(\boldsymbol{x}_0)$ to $q(\boldsymbol{x}_0)$ directly?

To answer this, let us remind ourselves that it is often a fruitful strategy to posit a latent generative process of the observed data and try to fit a model of that latent, generative process rather than fit the marginal distribution of the observed data directly. That is just what we are doing in the diffusion model framework! The idea of expanding the model from modeling a distribution over only a random variable representing the (noiseless) observed data, $\boldsymbol{x}_0$, to incorporate extra random variables, $\boldsymbol{x}_{1:T}$, defines a generative, latent variable model of the observed data. It turns out, this latent variable model resembles a variational autoencoder (VAE)!

As a brief review, recall that in the VAE framework, we assume that every data item/object that we wish to model, $\boldsymbol{x}$, is associated with a latent variable $\boldsymbol{z}$. We specify an inference model, $q_\phi(\boldsymbol{z} \mid \boldsymbol{x})$, that approximates the posterior distribution $p_\theta(\boldsymbol{z} \mid \boldsymbol{x})$. Note that $q_\phi(\boldsymbol{z} \mid \boldsymbol{x})$ is parameterized by a set of parameters $\phi$. One can view $q_\phi(\boldsymbol{z} \mid \boldsymbol{x})$ as a sort of encoder; given a data item $\boldsymbol{x}$, we encode it into a lower-dimensional vector $\boldsymbol{z}$. We also specify a generative model, $p_\theta(\boldsymbol{x} \mid \boldsymbol{z})$, that given a lower-dimensional, latent vector $\boldsymbol{z}$, we can generate $\boldsymbol{x}$ by sampling. If we have encoded $\boldsymbol{x}$ into $\boldsymbol{z}$, sampling from the distribution $p_\theta(\boldsymbol{x} \mid \boldsymbol{z})$ will produce objects that resemble the original $\boldsymbol{x}$. Thus $p_\theta(\boldsymbol{x} \mid \boldsymbol{z})$ can be viewed as a decoder. This process is depicted schematically below:

Now, compare this setup to the setup we have described for the diffusion model:

These figures were adapted from this blog post by Angus Turner.

In the case of a diffusion model, we have an observed item $\boldsymbol{x}_0$ that we iteratively corrupt into $\boldsymbol{x}_T$. In a way, we can view $\boldsymbol{x}_T$ as a latent representation associated with $\boldsymbol{x}_T$ in a similar way that $\boldsymbol{z}$ is a latent representation of $\boldsymbol{x}$ in the VAE. Note that this is a “hierarchical” VAE since we do not associate a single latent variable with each $\boldsymbol{x}_0$, but rather a whole sequence of latent variables $\boldsymbol{x}_1, \dots, \boldsymbol{x}_T$.

Moreover, the training objectives between the traditional VAE and this “hierarchical” VAE are identical. In the case of the traditional VAE, our goal is to minimize the expectation of the KL-divergence from $p_\theta(\boldsymbol{z} \mid \boldsymbol{x})$ to $q_\phi(\boldsymbol{z} \mid \boldsymbol{x})$, which we do so by maximizing the expectation of the ELBO:

\[\text{ELBO}_{\text{VAE}}(\phi, \theta) := E_{z \mid x \sim q_\phi} \left[ \log \frac{p_\theta( \boldsymbol{x}, \boldsymbol{z})}{q_\phi(\boldsymbol{z} \mid \boldsymbol{x})} \right]\]In the case of the diffusion model, we seek to minimize the KL-divergence from $p_\theta(\boldsymbol{x}_0, \dots, \boldsymbol{x}_T)$ to $q_(\boldsymbol{x}_0, \dots, \boldsymbol{x}_T)$, which can be maximized by optimizing the expectation of the following ELBO:

\[\text{ELBO}_{\text{Diffusion}}(\theta) := E_{\boldsymbol{x}_{1:T} \mid \boldsymbol{x}_0 \sim q}\left[ \log\frac{p_\theta (\boldsymbol{x}_{0:T}) }{q(\boldsymbol{x}_{1:T} \mid \boldsymbol{x}_0) } \right]\]While the analogy between VAEs and denoising diffusion models is helpful for drawing connections between ideas and gaining intuition, the analogy breaks down in a few key areas:

- The “encoder” model in the diffusion model, $q_(\boldsymbol{x}_0, \dots, \boldsymbol{x}_T)$, has no parameters. Rather, it is simple diffusion process that adds noise progressively to $\boldsymbol{x}$ until it turns into pure noise. Thus, the “latent representation” output by this “encoder” is rather meaningless – it’s just noise! Because it is just noise, it cannot be reconstructed (“decoded”) back to $\boldsymbol{x}$. In contrast, the encoder model in a VAE, $q_\phi(\boldsymbol{z} \mid \boldsymbol{x})$, is a true “encoder” in the sense that it outputs a meaningful latent variable $\boldsymbol{z}$ that stores the necessary information needed to reconstruct $\boldsymbol{x}$ (which can be performed by the decoder).

- In a VAE, we optimize the ELBO with respect to, $\phi$, the parameters of $q$, which can be interpreted as doing variational inference to approximate the posterior over $\boldsymbol{z}$ conditioned on $\boldsymbol{x}$. In a diffusion model, $q$ has no parameters and thus, our optimization of the ELBO cannot be truly interpreted as doing variational inference. Rather, because we only optimize with respect to $\theta$, we can only interpret the optimization procedure as performing approximate maximum likelihood that maximizes a lower bound of $\log p_\theta(\boldsymbol{x})$.

4. As breaking up a difficult problem into many easier problems

Another, more high-level, reason why diffusion models tend to perform better than other methods, such as variational autoencoders, is that diffusion models break up a difficult problem into a series of easier problems. That is, unlike variational autoencoders, where we train a model to produce an object all at once, in diffusion models, we train the model to produce the object step-by-step. Intuitively, we train a model to “sculpt” an object out of noise in a step-wise fashion rather than generate the object in one fell-swoop.

This step-wise approach is advantageous because it enables the model to learn features of objects at different levels of resolution. At the end of the reverse diffusion process (i.e., the sampling process), the model identifies broad, vague features of an object within the noise. At later steps of the reverse diffusion process, it fills in smaller details of the object by removing the last remaining noise.

Appendix

Derivation 1 (Deriving an upper bound over $KL(q(\boldsymbol{x}_0) \ \vert\vert \ p_\theta(\boldsymbol{x}_0)))$:

\[\begin{align*}KL(q(\boldsymbol{x}_{0:T}) \ \vert\vert \ p_\theta(\boldsymbol{x}_{0:T})) &= E_{\boldsymbol{x}_{0:T} \sim q} \left[ \log \frac{q(\boldsymbol{x}_{0:T})}{p_\theta(\boldsymbol{x}_{0:T})} \right] \\ &= E_{\boldsymbol{x}_{0:T} \sim q} \left[ \log \frac{q(\boldsymbol{x}_{1:T} \mid \boldsymbol{x}_0)q(\boldsymbol{x}_0)}{p_\theta(\boldsymbol{x}_{1:T} \mid \boldsymbol{x}_0)p_\theta(\boldsymbol{x}_0)} \right] \\ &= E_{\boldsymbol{x}_{0:T} \sim q} \left[ \log \frac{q(\boldsymbol{x}_{1:T} \mid \boldsymbol{x}_0)}{p_\theta(\boldsymbol{x}_{1:T} \mid \boldsymbol{x}_0)} \right] + E_{\boldsymbol{x}_{0} \sim q} \left[ \log \frac{q(\boldsymbol{x}_0)}{p_\theta(\boldsymbol{x}_0)} \right] \\ &= E_{\boldsymbol{x}_0 \mid q} \left[ E_{\boldsymbol{x}_{1:T} \mid \boldsymbol{x}_0 \sim q} \left[ \log \frac{q(\boldsymbol{x}_{1:T} \mid \boldsymbol{x}_0)}{p_\theta(\boldsymbol{x}_{1:T} \mid \boldsymbol{x}_0)} \right]\right] + E_{\boldsymbol{x}_{0} \sim q} \left[ \log \frac{q(\boldsymbol{x}_0)}{p_\theta(\boldsymbol{x}_0)} \right] \\ &= E_{\boldsymbol{x}_0} \left[ KL(q(\boldsymbol{x}_{1:T} \mid \boldsymbol{x}_0) \ \vert\vert \ p_\theta(\boldsymbol{x}_{1:T} \mid \boldsymbol{x}_0)) \right] + KL(q(\boldsymbol{x}_0) \ \vert\vert \ p_\theta(\boldsymbol{x}_0)) \\ &\geq KL(q(\boldsymbol{x}_0) \ \vert\vert \ p_\theta(\boldsymbol{x}_0)) \end{align*}\]The inequality follows from the fact that KL-divergence is always positive.