Demystifying Euler’s number

Published:

Euler’s number $e := 2.71828\dots$ has, to me, always been a semi-mysterious number. While I understood many facts about $e$, I never felt I ever truly understood what it really was – it’s core essence so to speak. I believe that part of the reason for my confusion is that $e$ is often taught coming from two seemingly different perspectives: Either it is introduced in the context of compound interest or it is introduced in the context of calculus as being the base of the exponential function whose derivative is itself. Thanks to an excellent explanation by Grant Sanderson’s 3Blue1Brown video, I now better understand this constant and how these two perspectives relate to one another. In this blog post, I will attempt to describe, in my own words, my understanding of Euler’s number and expound on Sanderson’s explanation.

Introduction

Euler’s number $e := 2.71828\dots$ has, to me, always been a semi-mysterious number. While I understood many facts about $e$, I never felt I ever truly understood what it really was – it’s core essence so to speak. I believe that part of the reason for my confusion is that $e$ is often taught coming from two seemingly different perspectives. Specifically, $e$ is introduced in one of two ways:

- As a constant that arises from deriving the formula for continuously compounded interest

- As the base of an exponential function whose derivative is the value of the function itself. That is, it is the constant, $e$, such that $\frac{de^x}{dx} = e^x$.

For a long time, I had trouble seeing how these two perspectives of $e$ were related to one another. Moreover, I didn’t have an understanding for why $e$ appears so often in equations across science and mathematics. In context of my prior blog post on “seeing concepts in 3D”, I didn’t have a “3D image” in my mind for how these two different “2D projections” of $e$ formed a cohesive “3D” concept.

With the help of Grant Sanderson’s excellent 3Blue1Brown video, I feel now that I have a much better understanding for it’s essence. In this blog post, I will attempt to describe, in my own words, my understanding of Euler’s number and expound on his explanation by attempting to tie together the two aforementioned perspectives of $e$.

To spoil the punchline, Euler’s constant, at its most abstract and fundamental level, is a number that describes all exponential functions – that is, functions of the form $f(x) := a^x$. In a very loose analogy, $e$ is to exponential functions as $\pi$ is to circles. They both are constants that describe some fundamental characteristic of a family of foundational mathematical structures (i.e., circles and exponential functions respectively). With this most fundamental understanding, we can tie together the two aforementioned perspectives of $e$.

$e$ describes the essence of exponential functions

At its most abstract and fundamental level, $e$ is a number that can be used to naturally represent all exponential functions. To arive at this understanding, let’s first discuss what it means for a function to be an exponential function.

To review, exponential functions are functions of the form:

\[f(x) := a^x\]for some constant $a$. Exponential functions do not only grow, but their growth also grows. When plotted, they look like the following:

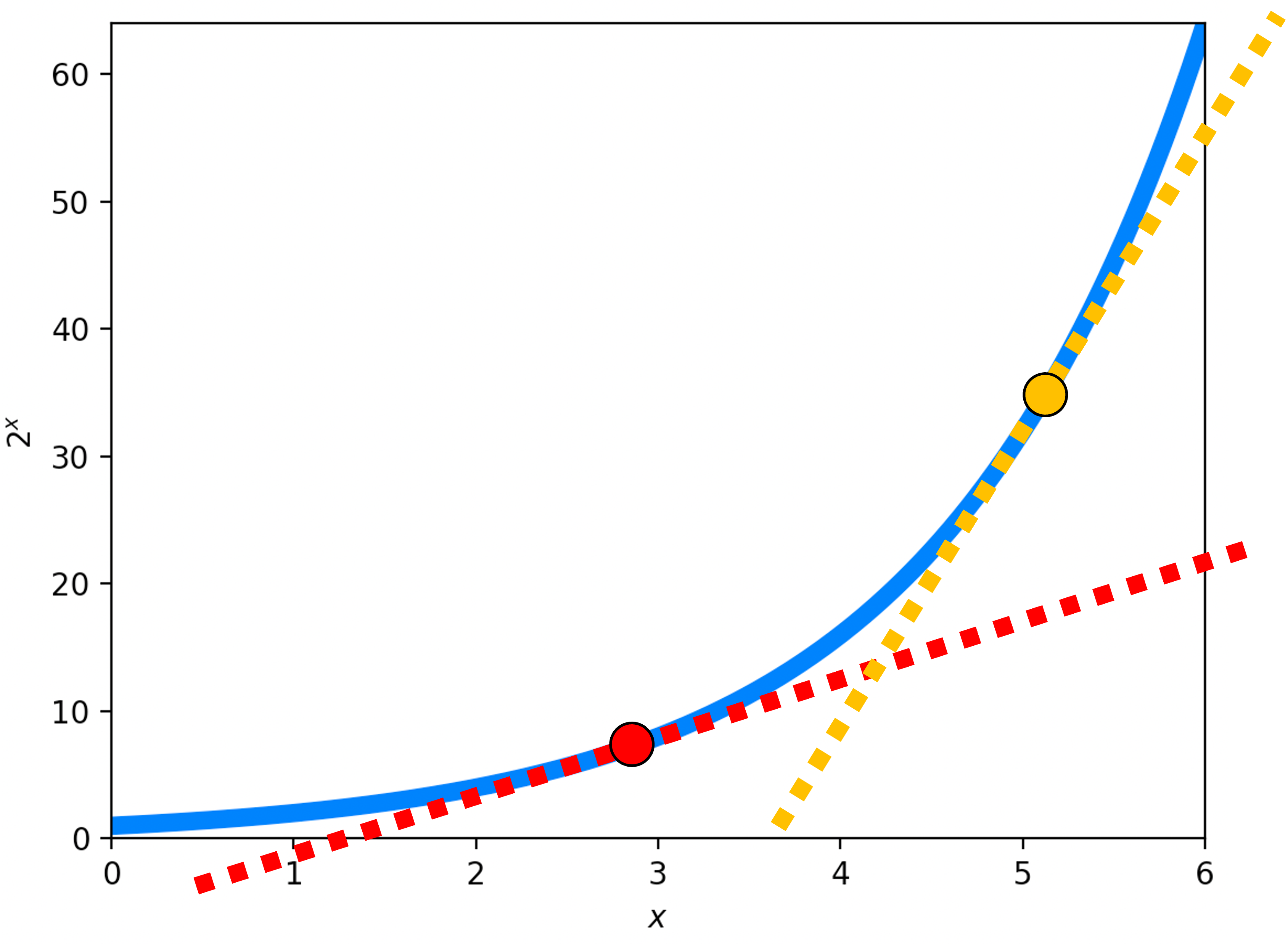

The key characteristic of exponential functions – the very characteristic that defines exponential functions – is that their growth grows linearly with the value of the function itself. Stated more rigorously, an exponential’s derivative is proportional to the value of the function itself. That is:

\[\frac{da^x}{dx} = Ka^x\]where $K$ is some constant that is determined by $a$.

That is, for all values of $x$, the derivative of $a^x$ is simply $a^x$ itself multiplied by some constant $K$. One can gain intuition for this fact by simply observing the function’s curve; The bigger is $a^x$ the steeper is the rate of change:

Let’s prove this fact more rigorously by starting with the definition of the derivative of $a^x$:

\[\begin{align*}\frac{da^x}{dx} &= \lim_{h \rightarrow 0} \frac{a^{x+h} - a^x}{h} \\ &= \lim_{h \rightarrow 0} \frac{a^xa^h - a^x}{h} \\ &= a^x \underbrace{\lim_{h \rightarrow 0} \frac{a^h - 1}{h}}_{K} \end{align*}\]Note, that the derivative of $a^x$ is simply $a^x$ scaled by a constant:

\[K := \lim_{h \rightarrow 0} \frac{a^{h} - 1}{h}\]Moreover, we see that this constant is determined by the value of $a$ – that is, it is a function of $a$. We can make the dependence of $K$ on $a$ by write this constant as a function of $a$:

\[k(a) := \lim_{h \rightarrow 0} \frac{a^{h} - 1}{h}\]Defining Euler’s number

Given our newfound understanding of exponential functions as functions whose derivative is proportional to themselves, a natural question that follows is: What exponential function, $a^x$, yields a constant of 1? That is, for what value of $a$ do we have $k(a) = 1$? It may not surprise you to learn that it’s Euler’s number!

That is, $e$ is the value for $a$ that satisfies the following equation:

\[1 = k(a) = \lim_{h \rightarrow 0} \frac{a^{h} - 1}{h}\]Said differently, Euler’s number is the base of the exponential function for which the derivative of that exponential function is the exponential function itself:

\[\frac{de^x}{dx} = e^x\]In a sense, $e$ defines the “base” exponential function; By “base” I mean the exponential function whose rate of change is itself (i.e., whose constant of proportionality is 1).

Of course, this fact does not actually tell us how to calculate $e$’s value. To calculate $e$’s value, we need to derive an alternative formula for $f(x) := e^x$ that does not contain $e$ and then plug $x := 1$ into this formula. We do so by first noting that $f’(x) = f(x)$ is a first-order differential equation. Coupling this differential equation with the fact that $f(0) = e^0 = 1$, we realize this is an initial value problem that can be solved using the Euler Method. If we do so, we find that

\[f(x) = e^x = \lim_{n \rightarrow \infty} (1 + \frac{x}{n})^n\]See Theorem 1 in the Appendix to this post for the complete derivation.

Plugging in $x := 1$, we find that $e$ can be expressed as a limit that enables us to compute numerical approximations of its value:

\[e = \lim_{n \rightarrow \infty} \left(1 + \frac{1}{n}\right)^n\]We can calculate ever closer approximations to $e$ by simply plugging in larger and larger values for $n$. If we do so, we find that $e \approx 2.71828$.

All exponential functions can be expressed in a more intuitive way with $e$

This fact about $e$ – that it is the base of the exponential function whose derivative is itself – does not quite explain why $e$ is so ubiquitous. Why do we see so many equations involving $e$?

The answer is that $e$ can be used to describe all exponential functions in a more intuitive and “natural” way. Thus, any equation that relates to exponential functions will likely involve $e$! It is sort of similar to how any equation that involves rotations or circles will usually involve $\pi$.

To see why, say we have some exponential function $a^x$. As we showed above, the derivative of $a^x$ is proportional to $a^x$ with some constant of proportionality given by $k(a)$. This value, $k(a)$, would need to be computed. Is there a way to express $a^x$ using $k(a)$ so that this value is obvious from the expression? Yes! It is simply,

\[a^x = e^{k(a) x}\]To see why, first note that

\[a^x = e^{\log a^x} = e^{x \log a}\]Here we see that $a^x$ has been re-written as $e^{x \log a}$ where $\log a$ is simply a constant. It turns out that this constant, $\log a$, is really just $k(a)$. We know this because if we take the derivative of $e^{x \log a}$, we get

\[\begin{align*}\frac{d a^x}{dx} &= \frac{d e^{x \log a}}{dx} \\ &= (\log a) e^{x \log a} && \text{Chain rule} \\ &= (\log a) a^x \end{align*}\]That is, $\log a$ is that very constant of proportionality that we defined $k(a)$ to be!

Because every value for $a$ is associated with a unique constant $k(a)$, we can express all exponential functions using the constant $k(a)$ instead of $a$. That is, by using $e^{k(a) x}$ instead of $a^x$. Arguably, this form makes the exponential easier to interpret: Whenever you come upon an exponential function, $f(x) := e^{Kx}$, the rate of change of $f(x)$ at $x$ is simply the value of this function scaled by the constant $K$.

In a very loose analogy, $e$ is to exponential curves as $\pi$ is to circles. Where $\pi$ is a constant that describes all circles, $e$ describes all exponential functions. Specifically, $e$ describes the sort of “origin exponential function” – that is, the exponential function from which all other exponential functions can be described in reference to.

$e$ arises in a formula for continously compounded interest

Euler’s number was actually discovered first by Jacob Bernoulli as it relates to compound interest. In fact, $e$ is often introduced to students in this way and it’s only discussed in relation to exponential functions in more advanced treatments of the topic. Let us now approach $e$ from the perspective of compound interest. We will later connect it from this perspective back to exponential functions.

Say we have $P$ dollars, as principal, that we lend out at an interest rate $r$ over some unit of time (e.g., one year). After this amount of time, we would have the following amount of money:

\[\begin{align*}\text{Total} &:= P + rP \\ &= P(1+r) \end{align*}\]Note that because the interest wasn’t paid out until the end of the perscribed time, the interest itself was not given the opportunity to earn any money. One way to fix this would be to have that interest “compound” – that is, be paid out at set increments and added to the principal.

Let’s now say that interest compounds every half unit of time (e.g., every six months instead of every year). Then at the halfway point, when the interest compounds for the first time, the $P$ dollars would earn $\frac{r}{2}P$ and this $\frac{r}{2}P$ could then earn interest for the remaining half of time. We can derive the total amount of money we have left as follows: Let $P_1$ be the money we have after interest compounds the first time. It compounds at a rate of $r / 2$ because we compounded it at half the time interval (i.e., the first half of time):

\[\begin{align*}P_1 &:= P + \frac{1}{2}P \\ &= P\left(1+\frac{r}{2}\right) \end{align*}\]We can calculate the total now by treating $P_1$ as the “principal” starting just after the interest compounds the first time from which it will earn at a rate of $r / 2$ (because it compounds over the second half of time):

\[\begin{align*}P_2 &:= P_1 + \frac{1}{2}P_1 \\ &= P_1\left(1+\frac{r}{2}\right) \end{align*}\]Plugging in $P_1$, we get the final total as:

\[\begin{align*} \text{Total} &:= P_1\left( 1+\frac{r}{2} \right) \\ &= P\left(1+\frac{r}{2}\right)\left(1+\frac{r}{2}\right) \\ &= P\left(1+ \frac{r}{2}\right)^{2} \end{align*}\]We can play this game again and now instead of compounding twice, it compounds three times. In fact, we can increase the number of times that the money compounds to any arbitrary number, $n$, and we will find that the total we end up with at the end will be:

\[\text{Total} := P\left(1-\frac{r}{n}\right)^n\]Before we move on, let’s generalize this formula slightly and consider the total we would earn after $t$ units of time and derive a formula that takes into account $t$. The derivation will be similar to how we derived the formula above that takes into account the number of times interest compounds per unit of time, $n$. We’ll start by considering $t = 2$. Let’s let $P_1$ be the interest earned after $t = 1$:

\[\begin{align*}P_1 := P\left(1-\frac{r}{n}\right)^n \end{align*}\]Similar to before, we can calculate the total by treating $P_1$ as the “principal” starting after the first unit of time and plugging in $P_1$:

\[\begin{align*}\text{Total} &:= P_1 \left(1-\frac{r}{n}\right)^n \\ &= P\left(1-\frac{r}{n}\right)^n \left(1-\frac{r}{n}\right)^n \\ &= P\left(1-\frac{r}{n}\right)^{2n}\end{align*}\]We can perform this derivation for any value of $t$ and we would find that

\[\text{Total} := P\left(1-\frac{r}{n}\right)^{nt}\]Now that we’ve generalized our formula to take into account $t$, let’s now ask the question: What if we compound the interest _every possible instant –? That is, instead of compounding $n$ times, it compounds an infinite number of times: every possible instant. We can derive this formula by taking the limit of the above formula as $n$ approaches infinity:

\[\begin{align*}\text{Total} &:= \lim_{n \rightarrow \infty} P\left(1-\frac{r}{n}\right)^{tn} \\ &= P \lim_{n \rightarrow \infty} \left(1-\frac{r}{n}\right)^{nt} \\ &= Pe^{rt} && \text{Theorem 1} \end{align*}\]This is simply an exponential function $e^{rt}$ scaled by $P$!

Connecting the dots

So far, we have derived $e$ from two alternative perspectives:

- As being the base of the exponential function whose derivative is itself

- As a constant used in a formula to compute continuously compounding interest

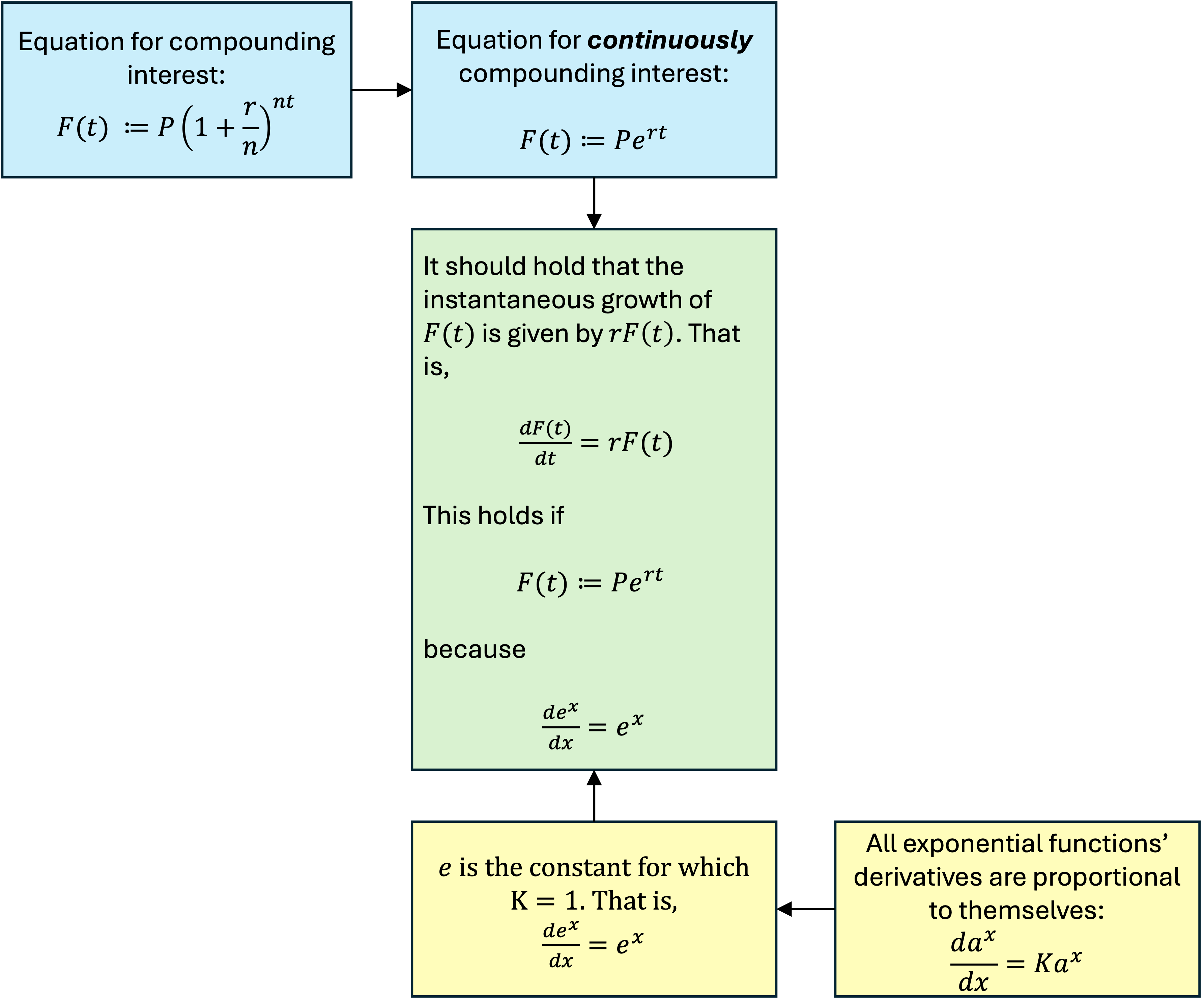

Let’s wrap up this discussion by describing explicitly how these two ideas are connected. Let $F(t)$ be a function that tells us how much money we have during the duration of a loan whose interest is continously compounding. Furthermore, let’s pretend for a moment that we don’t know the equation $F(t) := Pe^{rt}$.

Intuitively, if interest is compounding continuously, then the instantaneous growth of $F(t)$ at $t$ should be given by the interest rate multiplied by however much money we currently have, which is given by $F(t)$. That is, we would naturally expect the instantaneous growth rate of our money to be $rF(t)$. Stated mathematically,

\[\frac{dF(t)}{dt} = r F(t)\]And indeed we see that if $F(t) := Pe^{rt}$, then we can apply the chain rule to find that

\[\begin{align*} \frac{dF(t)}{dt} &:= \frac{dPe^{rt}}{dt} \\ &=rPe^{rt} \\ &= r F(t) \end{align*}\]This only works because of the fact that $\frac{de^x}{dx} = e^x$! The full picture is illustrated in the following diagram:

Further Reading

Appendix

Theorem 1 (Value of $e$): The value for $e$ is given by the following limit:

Proof:

Let

\[f(x) := e^{x}\]and

\[f'(x) = \frac{df(x)}{dx}\]We know the following facts about $f(x)$:

\[\begin{align*}f(0) &= e^0 = 1 \\ f'(x) &= f(x) \end{align*}\]Note that $f’(x) = f(x)$ is a first-order differential equation and $f(0) = 1$ is an initial condition. Thus, given an arbitrary value for $x$, we can solve for $f(x)$ by solving this initial value problem. We can do so using the Euler Method.

In order to solve for $f(x)$, we will use Euler’s method with increments of $\Delta t := x/n$ for some number of increments $n$.

We first note that for an arbitrary value of $t$, we can approximate $f(t + \Delta t)$ via

\[f(t + \Delta t) \approx f(t) + \Delta t f'(t)\]Because $f’(t) = f(t)$, we have

\[\begin{align*}f(t + \Delta t) &\approx f(t) + \Delta t f'(t) \\ &= f(t) + \Delta t f(t) \\ &= f(t)(1 + \Delta t) \end{align*}\]Using this formula, we can solve for $f(x)$ by starting at $t := 0$ and stepping towards $f(x)$ at increments of $\Delta t := \frac{x}{n}$ using the equation above. For the first step, where $t := 0$, we have

\[\begin{align*}f(0 + \Delta t) &\approx f(0) (1 + \Delta t) \\ &= 1 + \frac{x}{n}\end{align*}\]Taking the second step, we have

\[\begin{align*} f\left(\frac{x}{n} + \Delta t\right) &\approx f\left(\frac{x}{n} \right) (1 + \delta t) \\ &= \left(1 + \frac{x}{n}\right) \left(1 + \frac{x}{n}\right) \\ &= \left(1 + \frac{x}{n}\right)^2 \end{align*}\]Extrapolating this all the way to $n$ steps, arriving at $f(x)$, we see that

\[\begin{align*}f(x) &= f\left( n\frac{x}{n} \right) \\ &= f\left( (n-1)\frac{x}{n} + \frac{x}{n} \right) \\ &= \left( 1 + \frac{x}{n} \right)^{n-1} \left( 1 + \frac{x}{n} \right) \\ &= \left( 1 + \frac{x}{n} \right)^{n} \end{align*}\]Finally, to derive $e$ itself, we plug in $x = 1$ and see that

\[f(1) = e^1 = e \approx \left( 1 + \frac{1}{n} \right)^{n}\]Note that, as $n \rightarrow \infty$, this formula will converge on the true value of $e$ and thus,

\[e = \lim_{n \rightarrow \infty} \left( 1 + \frac{1}{n} \right)^{n}\]$\square$