On cell types and cell states

Published:

The advent of single-cell genomics has brought about new efforts to characterize and catalog all of the cell types in the human body. Despite these efforts, the very definition of a “cell type” is under debate. In this post, I will discuss a conceptual framework for defining cell types as subsets of states in an underlying cellular state space. Moreover, I will link the cellular state space to biomedical ontologies that attempt to capture biological knowledge regarding cell types.

Introduction

With the advent of single-cell genomics, researchers are now able to probe molecular biology at the single-cell level. That is, scientists are able to measure some aspect of a cell, such as its transcriptome (RNA-seq) or its open chromatin regions (ATAC-seq), for thousands, and sometimes even millions of cells at a time. These new technologies have brought about new efforts to map and catalog all of the cell types in the human body. The premier effort of this kind is the Human Cell Atlas, an international consortium of researchers who have set themselves on the journey towards creating “comprehensive reference maps of all human cells—the fundamental units of life—as a basis for both understanding human health and diagnosing, monitoring, and treating disease.”

Of course, before one begins to catalog cell types, one must define what they mean by “cell type”. This has become a topic of hot debate. Before the age of single-cell genomics, a rigorous definition was usually not necessary. Colloquially, a cell type is a category of cells in the body that performs a certain function. Commonly, cell types are considered to be relatively stable. For example, a cell in one’s skin will not, as far as we know, spontaneously morph into a neuron.

Unfortunately, researchers found that such a fuzzy definition does not suffice as a foundational definition from which one could go on to create “reference maps”. One reason for this is that the resolution provided by single-cell technologies enables one to find clusters of similar cells, that one may deem to be a “cell type”, at ever more extreme resolutions. For example, Svennson et al. (2021) found that as researchers measure more cells, they tend to find more “cell types”. Here’s Figure 5 from their preprint:

Moreover, we now know that cells are actually pretty plastic. While skin cells naturally don’t morph into neurons, they can be induced to morph into neurons using special treatments. Moreover, cells do switch their functions relatively often. A T cell in a lymph node can “activate” to fight an infection. Do we call transient cell states “cell types”? Do we include them in our catalog?

Lastly, there is the question of how to handle diseased cells. Is a neuron that is no longer able to perform the function that a neuron usually performs still a neuron? Does a “diseased” neuron get its own cell type definition? What criteria do we use to determine whether a cell is “diseased”?

There is not yet an agreement in the scientific community on how to answer these questions. Nonetheless, in this post, I will convey a perspective, which combines many existing ideas in the field, that will attempt to answer them. This perspective is a mental framework for thinking about cell types, cell states, and what it means to “catalog” a cell type.

The cellular state space

First, let’s get the obvious out of the way: the concept of “cell type” is human-made. Nature does not create categories, rather, we create categories in our minds. Categories are fundamental building blocks of our mental processes. In nature, there are only cell states. That is, every cell simply exists in a certain configuration. It is expressing certain genes. It is comprised of certain proteins. Its genome is chemically and spatially configured in a specific way. Moreover, cells change their state over time. A cell is in a constant state of flux as it goes about its function and responds to external stimuli.

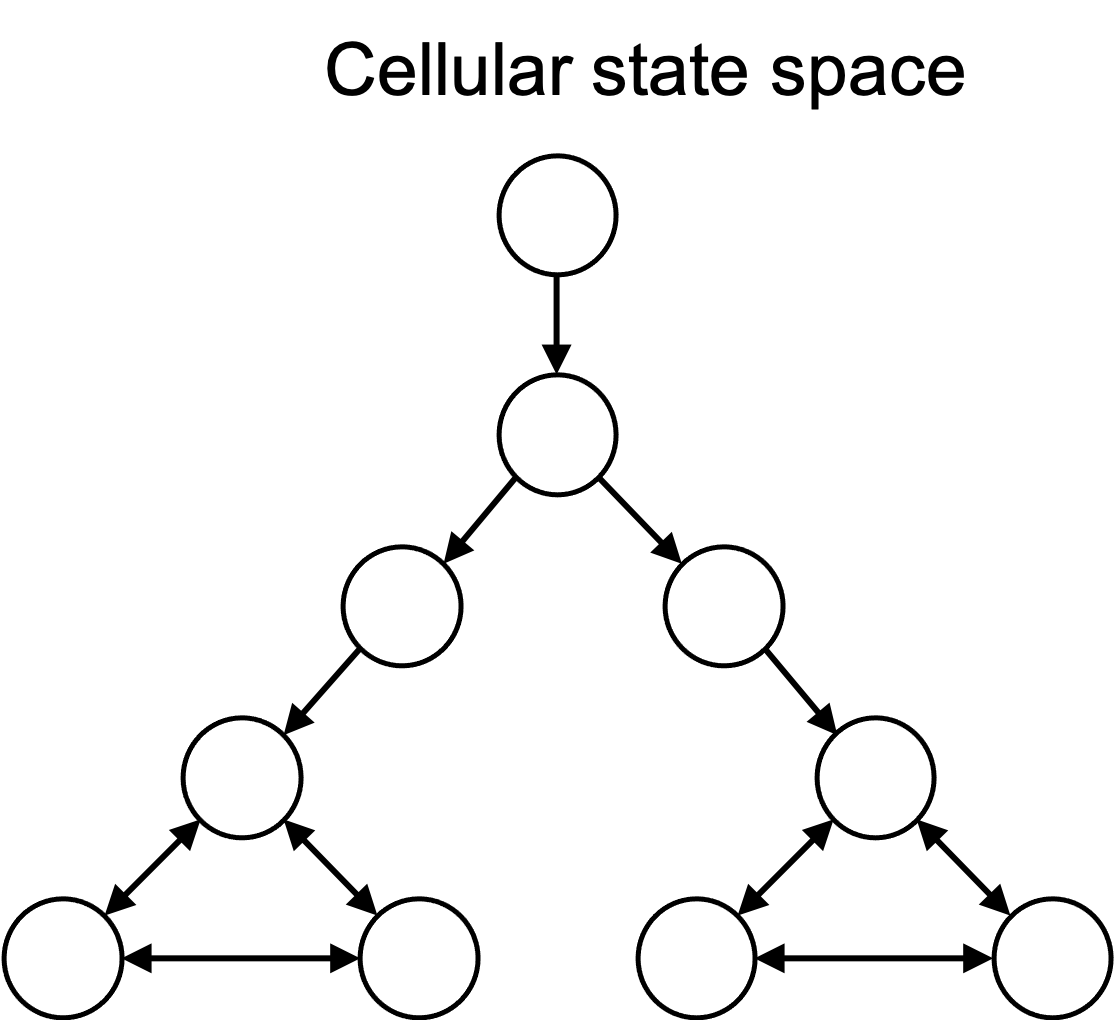

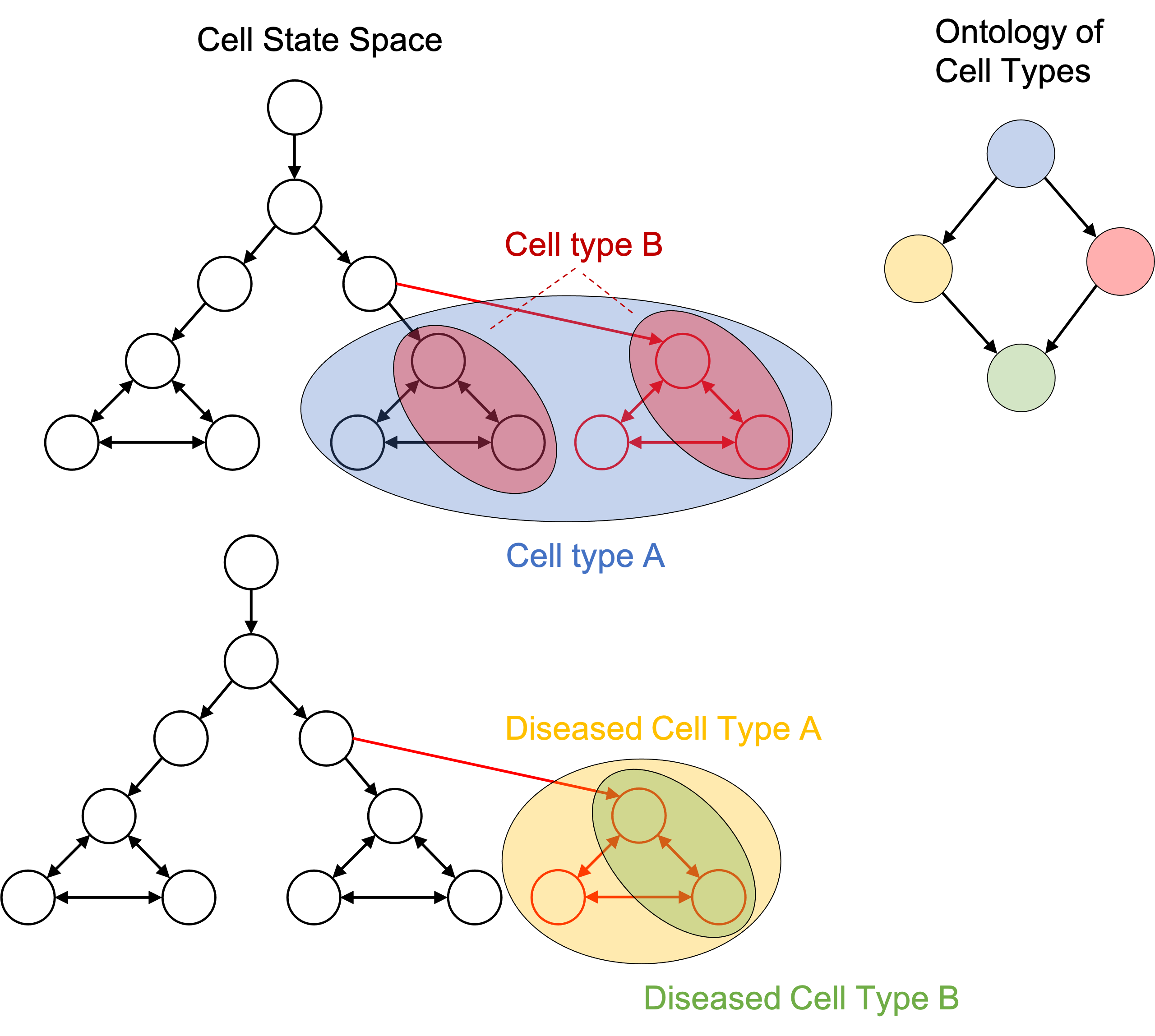

In computer science parlance, we can think about the set of cell states as a state space. That is, the cell always exists in a specific, single state at a specific time, and over time it transitions to new states. If these states are finite (or countable), one can view the state space as a cellular automaton, where the state space can be represented by a graph, in which nodes in the graph are states and edges are transitions between states. This is depicted in the figure below:

In reality, the state space of a cell is continuous, but for the purposes of this discussion, we will use the simplification that the state space is discrete and can be represented by a graph.

This idea is not new. In fact there is a whole subfield of computational biology that seeks to model cells, and other biological systems, as computational state spaces.

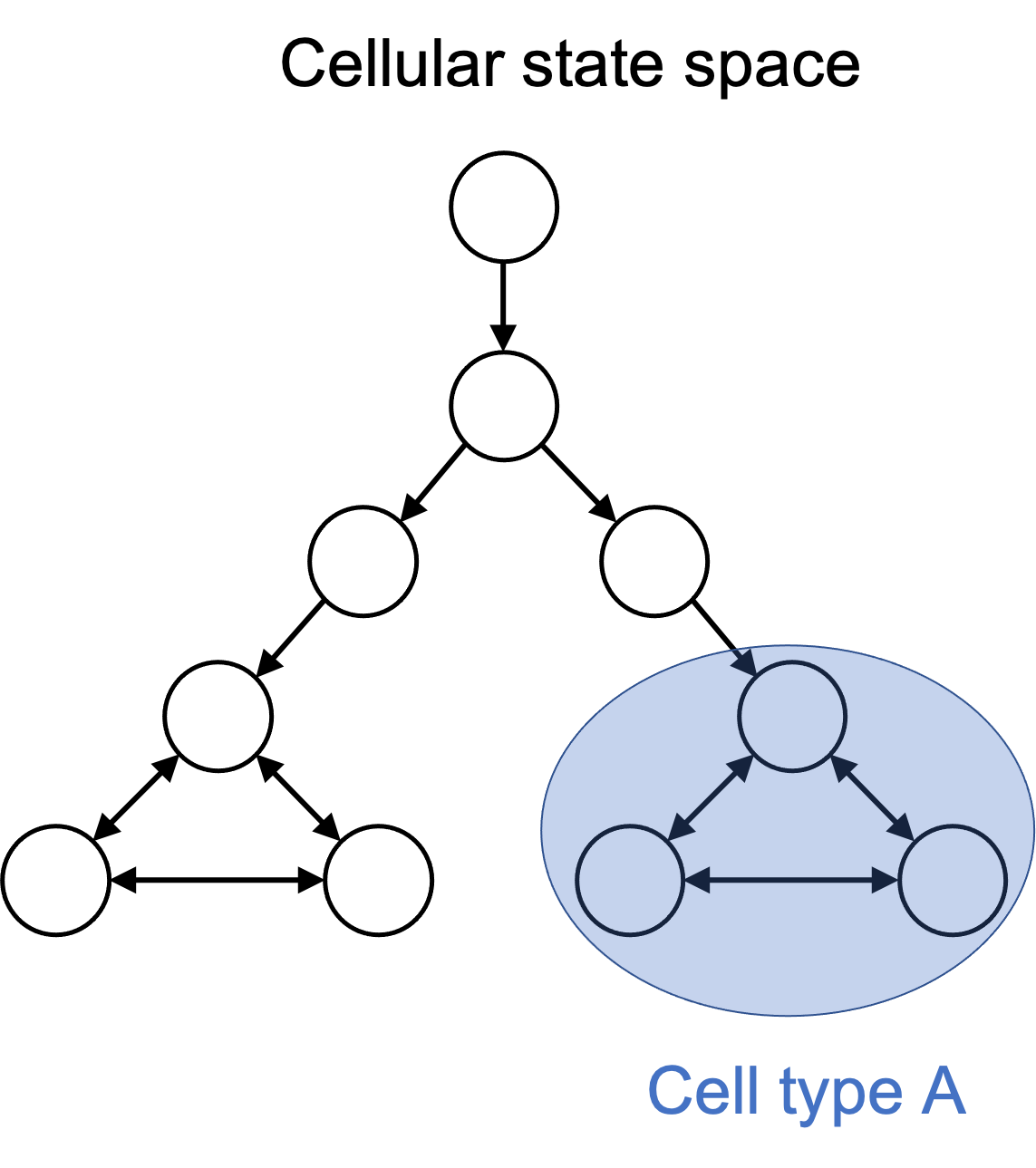

A cell type is a subset of states

I argue that one can define a cell type to simply be a subset of cell states in the cellular state space. For example, when one talks about a “T cell”, they are inherently talking about all states in the cell state space in which the cell is performing a function that we have named “T cell”. Importantly, a cell type is a human-made partition on the cellular state space. This is depicted in the figure below:

Importantly, one can define cell types arbitrarily. In fact, any member of the power set of cell states could be given a name and considered to be a cell type! Of course, as human beings with particular goals (such as treating disease), only a very small number of subsets of the state space are useful to think about. Thus, it might not be a good idea to go ahead and create millions of cell types, even though we could.

Cataloging cell types with ontologies

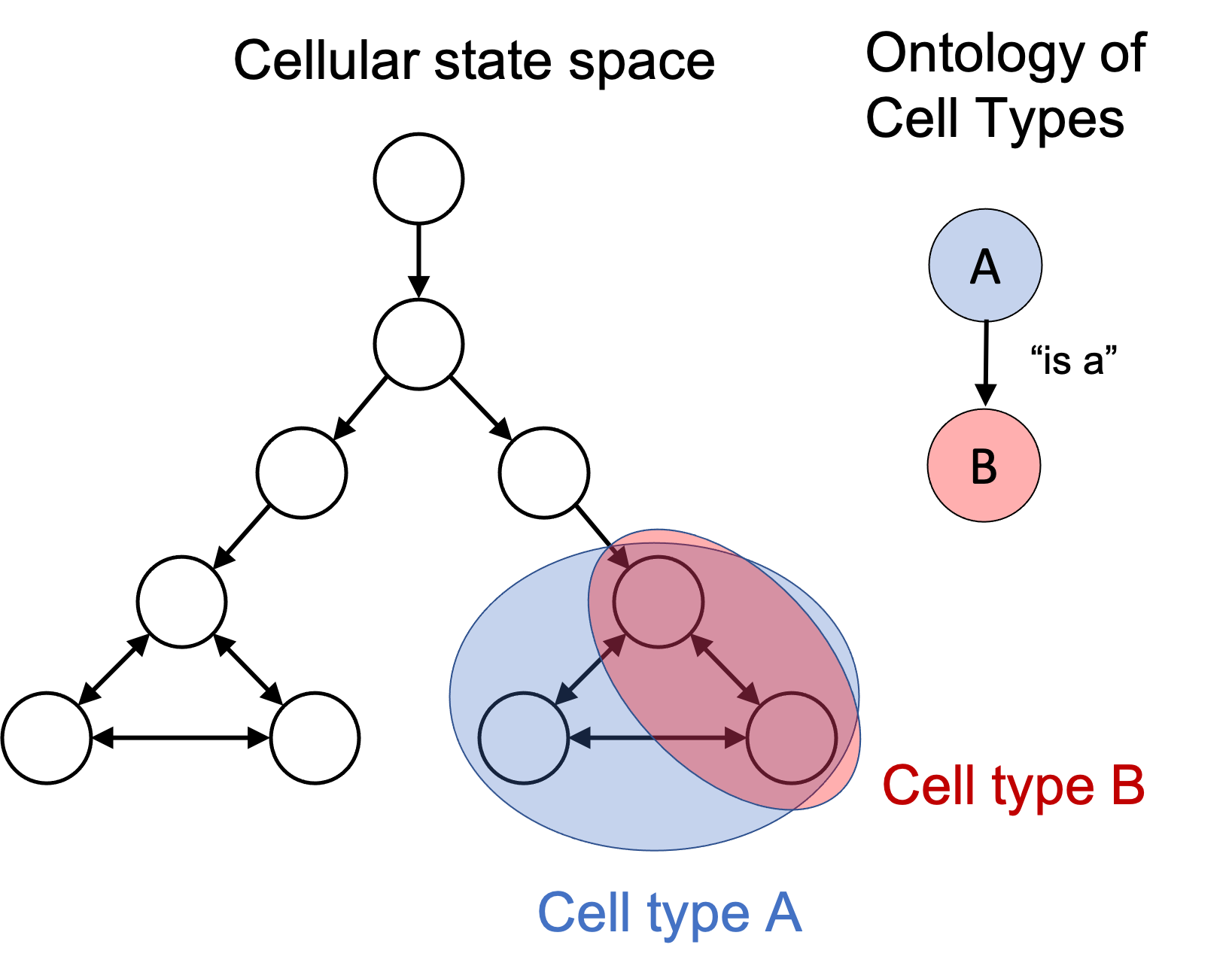

A big question is, how do we organize all of these cell types? One idea that I find particularly compelling is to use knowledge graphs or ontologies (the two concepts are very similar, with a few subtle differences). In such graphs, each node represents a concept and an edge between two concepts represents a relationship between those two concepts. For example, the subtype relationship between two concepts is often denoted using an edge labelled as “is a” . For example, if we have a knowledge graph containing the nodes “car” and “vehicle”, we would draw an “is a” edge between them, which encodes the knowledge that, “every car is a vehicle.”

In the cellular state space, these “is a” edges are simply subset relationships. If one cell type’s set of states is a subset of another cell type’s set of states, then we can draw an “is a” edge between them in the cell type ontology. For example if we have “Cell Type B is a Cell Type A”, this means that any cell in the set of states labelled “Cell Type B” is also in the set of states labelled as “Cell Type A”. This is depicted in the figure below:

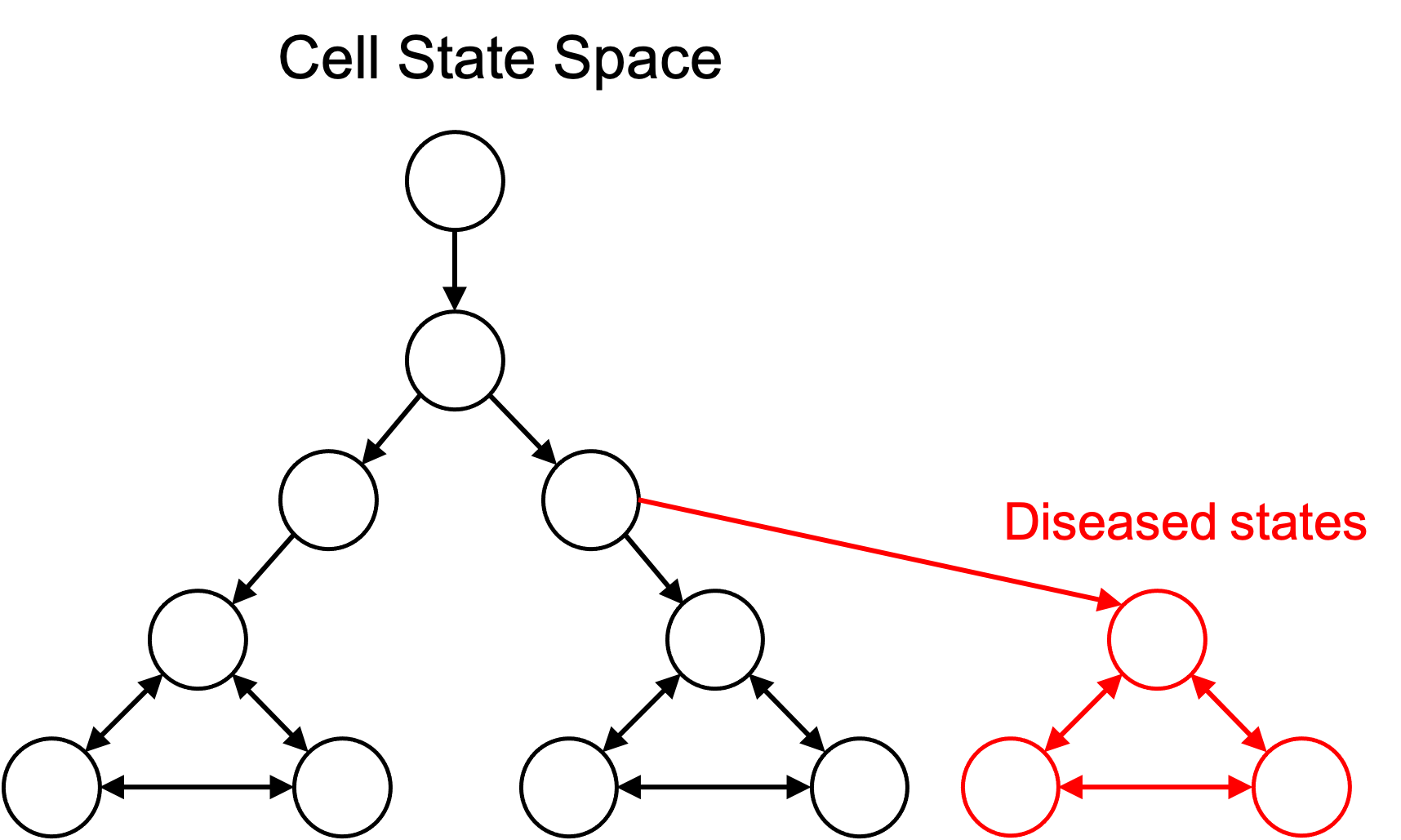

Viewing disease through the lense of cellular state spaces

The idea of defining cell types to be subsets of cell states enables one to define disease cell types. That is, a diseased cell type is simply a collection of cell states just like any other cell type. This is depicted in the figure below:

Because diseased cell types are represented in the same framework as any other cell type, we can add them to an ontology of cell types as discussed previously:

Viewing batch effects through the lense of cellular state spaces

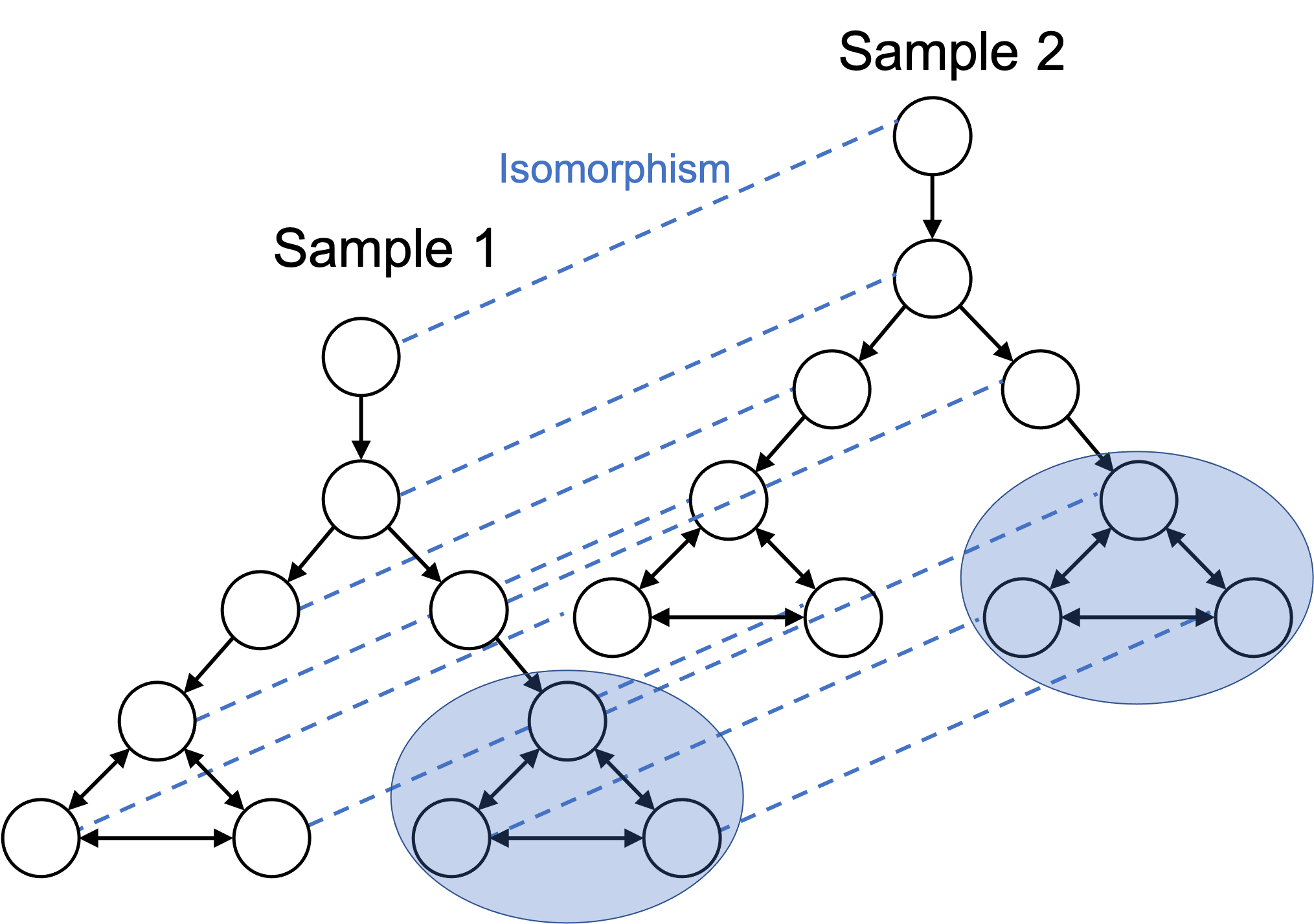

Another important point to keep in mind is that the subgraph of cell states used to define a given cell type need not be connected in the cellular state space. For example, one individual’s T cells are almost certainly in a slightly different state than another individual’s T cells owing to differences in genotype and environment. Nonetheless, we may still wish to call both of these cells “T cells”.

This may also occur in two samples of cultured cells. The two cell cultures may not be grown under the exact same conditions and thus, there may be a slight difference in the cellular states of the cells in the two cultures. Nonetheless, we may wish to still define the cells in the two cultures to be of the same cell types.

We do so as follows: we extend the cellular state space to include multiple individuals or multiple samples (i.e., multiple batches). This results in two disconnected, and approximately isomorphic subgraphs. This is depicted in the figure below:

From this angle, we can more rigorously define the common task in single-cell analysis that involves removing batch effects between two samples. That is, our goal is to find the isomorphism between the two cellular state spaces that the cells in the two samples are following. Of course, in practice, we don’t have access to the underlying cellular state space, so we are left to heuristics. (For example, Haghverdi et al. (2018) propose a method for detecting mutual nearest neighbors between cells that belong to two different batches and then uses these neighbors to transform the cells into a common space.)

Putting these ideas into practice

All of the ideas that I presented in this post are horribly simplified. In general, our knowledge of cellular function and the underlying state space of the biochemistry of cells is woefully incomplete and thus, it remains impossible to rigorously define a cell type as a set of cellular states as I discussed here. Nonetheless, I find it to be a useful mental model for thinking about cell types, cell states, and for placing open problems in bioinformatics into a common conceptual framework.

Further reading

- An article by Cole Trapnell discussing the differences between cell types and cell states: https://genome.cshlp.org/content/25/10/1491.full.html

- An article by Samantha Morris on the ongoing discussion on how to think about cell types and cell states: https://dev.biologists.org/content/146/12/dev169748.abstract

- Opinions on how to define a cell type: https://www.cell.com/cell-systems/pdf/S2405-4712(17)30091-1.pdf

- Human Cell Atlas: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5762154/

- An exploration of the distinction between cell type and cell state in Clytia Medusa by Tara Chari et al.: https://www.biorxiv.org/content/10.1101/2021.01.22.427844v2.full.pdf