Intuiting biology (Part 1: Order and chaos in the crowded cell)

Published:

Cells are crowded spaces packed with biomolecules colliding and interacting with one another. Despite this chaotic environment, biologists routinely describe intracellular functions using the clean mathematical language of networks. In this post I will attempt to reconcile these two seemingly contradictory perspectives of the cell. This post will serve as a first part in a series of blog posts I hope to write where I will collect and connect some of the works that have helped me better “intuit” biology as a person coming to biology from the field of computer science.

Introduction

As a computer scientist working in biomedical research, I have had to develop my biology knowledge on the fly. Over the course of this effort, there have been certain concepts, articles, and other bodies of work that led to notable step-functions in my ability to “intuit” biological systems. (Given the staggering complexity of biology, my use of the word “intuit” is quite strained here, but I digress). In this series of blog posts, I will collect some of these works and attempt to connect them together conceptually. I hope this series serves others who are on a similar journey as I am!

In the first post of this series, I will attempt to tie two seemingly contradictory ideas together:

- Cells are densely packed, chaotic places

- We can describe cellular processes using the clean language of graphs/networks

I will begin by discussing the visual depictions of cells by David S. Goodsell. Dr. Goodsell is a structural biologist at the Scripps Research Institute and Rutgers University and is well known for his scientifically accurate depictions of cells and the molecules that they are comprised of. His work is both educational and beautiful and helped expand my understanding of biology.

As I will discuss, Dr. Goodsell’s work highlights how densely packed, and seemingly chaotic the environments within cells are. The packed, chaotic nature of these environments seems to contradict the fact that biologists routinely describe cells using the clean, mathematical language of networks and graphs as used in the subfied of Network Biology. In this post, I will attempt to connect and renconcile these two perspectives of the cell.

Cells are absolutely packed

What struck me most from Dr. Goodsell’s work is how densely packed cells really are. Below is an example illustration that depicts the density of the cell:

This is a far cry from the image I had previously held of cells as a little, uncrowded “bags of water”. I believe this incorrect mental model was fomented in my mind by images like the following that are meant to teach the organelles found in the cell:

Though images like this are effective for teaching the different organelles found in cells, they imply that cells are empty (at least that was my impression). This was a misconception that I had held for a good portion of my computational biology journey.

A second thing that struck me was the interplay between order and chaos that exists within cells. As an example, see this illustration by Goodsell depicting the coronovirus lifecycle:

Notice that despite the messy distribution of proteins and other biomolecules, clear structures form (membranes, gradients, etc.). In the above picture we see, emerging from the chaos, the insidious formation of new viruses!

How order emerges from the chaos: connections to network biology

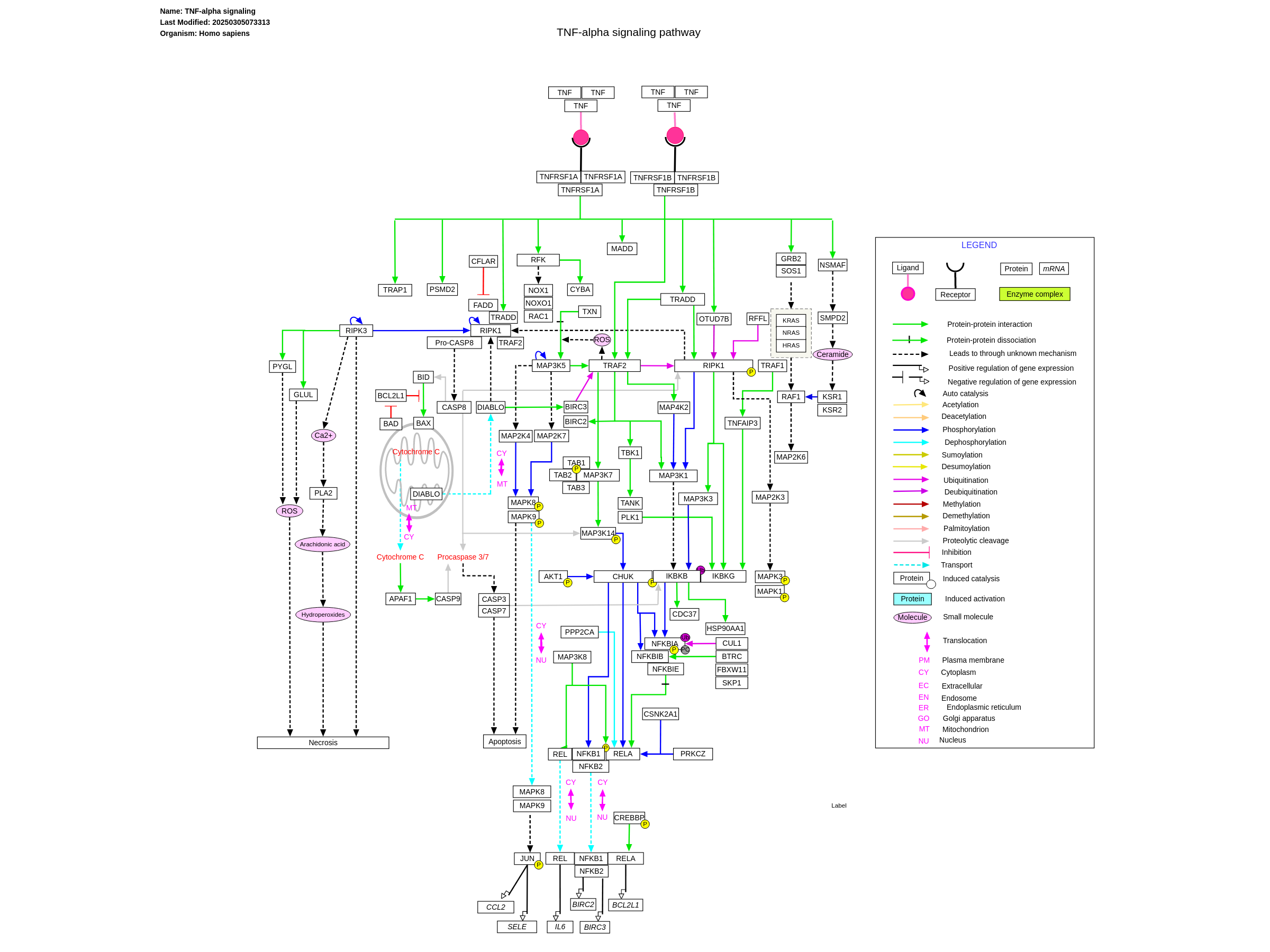

If you work in computational biology, there is little doubt that you have been exposed to concepts found in network biology. A common way to describe the biochemical processes that occur in cells is to depict and model these processes mathematically as networks or graphs. For example, protein-protein interaction networks are networks in which proteins form the nodes of the graph and an edge between two proteins indicates that those two proteins interact or bind with one another. Such protein interaction networks form signaling pathways in which the information-flow through the cell is mediated by cascading interactions between proteins and other molecules. For example, below is a depiction of the TNF-alpha signalling pathway, which is a signalling pathway used to modulate immune cell function:

Despite the cells being so crowded, the network model has proved to still be a powerful model for describing cellular functions. Why is this exactly?

As far as I understand, there are two “competing” phenomenon that are occuring within the cell that leads to the network model:

- Molecules move extremely fast inside cells leading to many opportunities for interaction

- Interactions will rarely occur between two biomolecules

First, despite the cell being so crowded, molecules move extremely fast within the cell and this gives them a lot of opportunity to meet one another. Our intuition, based on the macroscale in which we live, breaks down at at the subcellular scale. To try to grow some new intuition, let’s look at the numbers.

According to Ron Miley and Rob Phillips in Cell Biology by the Numbers, it takes about 10 seconds for a protein to traverse a HeLa cell. When considering the fact that every protein is moving in this manner, we realize that every few seconds, the arangement of proteins in the cell has completely changed (subject to compartmenalization within the cell).

This rearrangement is even more extreme for small molecules. In fact, in an e. coli bacterium, one can expect that every small molecule will collide with every single protein once per second! (Pretty mind boggling.) Now, Eukaryotic cells are much larger, but we can still expect a small molecule to meet every single protein within a short span of time.

Thus, if we have two biomolecules in the cell that can bind/interact (including proteins), we can deduce that they inevitably will interact within a fairly short span of time (again, subject to their compartmentalization within the cell). Thus, as far as I understand, the deterministic picture portrayed by a network diagram is actually fairly accurate!

Now, with this in mind, wouldn’t one expect many aberrant reactions and/or electrostatic binding? The answer is “no” for two main reasons: First, when considering small molecules in the cell, most chemical reactions have a very high activation energy and require a catalyst, such as an enzyme, to occur. Thus, though small molecules are colliding with eachother constantly, they are unlikely to interact. Second, when considering proteins (i.e., larger biomolecules), the targets that proteins bind to are hyperspecific. Thus, the specific pairs (or combinations) of proteins that actually interact with one another is an extremely small fraction of all possible pairs.

Putting this all together at a (very) high-level: molecules move extremely fast in the cell and will (roughly) meet every other molecule in the cell within a short span of time; however, the pairs of molecules that actually interact when they meet is extremely small. From these two facts, we gain a sense for how the network model emerges despite the packed and chaotic the environment within cells!