Three strategies for cataloging cell types

Published:

In my previous post, I outlined a conceptual framework for defining and reasoning about “cell types”. Specifically, I noted that the idea of a “cell type” can be viewed as a human-made partition on the universal cellular state space. In this post, I attempt to distill three strategies for partitioning this state space and agreeing on cell type definitions.

Introduction

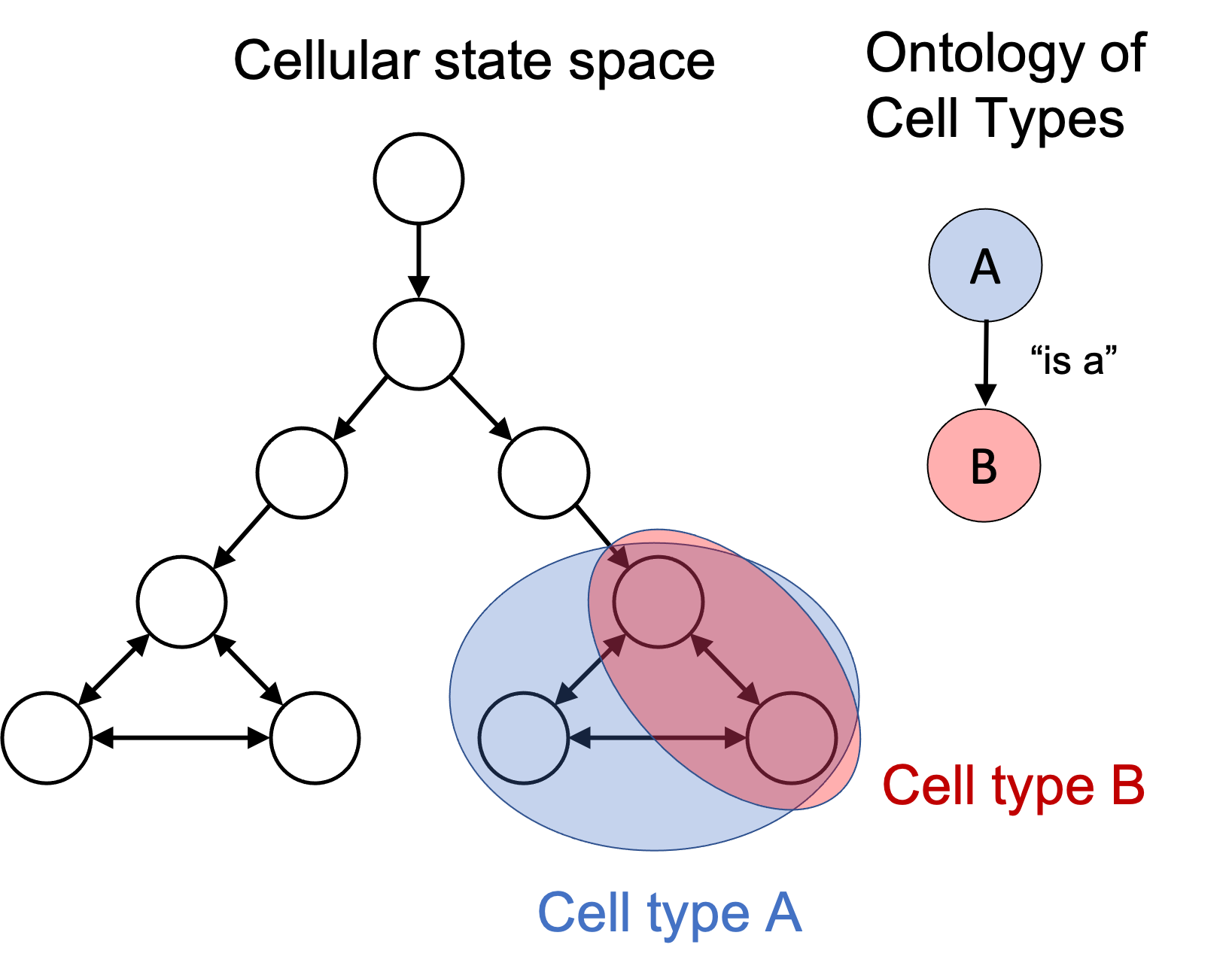

In my previous post, I outlined a conceptual framework for defining and reasoning about “cell types”. Specifically, I noted that the idea of a “cell type” can be viewed as a human-made partition on the universal cellular state space: the set of all possible states a living cell can exist in and the transitions between them. This idea can be summarized in the following figure:

In this framework, the task of cataloging cell types involves identifying “useful” subsets of cell states and giving those subsets names. Then, one can create a hierarchy of cell types by simply computing the subset-relationships between those sets of cell states.

While this framework is conceptually clean and simple, there are a number of problems with implementing it in the real world. These problems include:

- We don’t know the full cellular state space

- We don’t have a language for describing subsets of that state space

- We don’t have a way of agreeing on how to partition the state space

Problems 1 and 2 are hard, and I’ll save a discussion on these problems for later. In this post I will only discuss Problem 3: how do we agree on partitions of the state space. Said much more simply: how do we agree on a definition for a cell type.

In my opinion there are three core strategies that have been proposed by the scientific community; however, these ideas have taken different forms. In this post, I will attempt to tease out and more rigorously describe each of these strategies.

These strategies are:

- Every scientist for themself. Come up with your own cell type definition based on your own needs. In fact, this idea is embraced by a number of single-cell RNA-seq cell type classifiers such as Garnett. Garnett features a “zoo” of cell type classifiers that one can create and then use to label a new dataset.

- Crowdsourcing. In this strategy, one may look at all of the published genomics data out there in public repositories and use these data to come to a consensus of how the scientific community as a whole defines cell types. This is the core idea behind CellO, a cell type classification tool that I worked on that uses the collection of publicly available primary cell data to train cell type classifiers.

- Central authority. This is the idea behind the Human Cell Atlas. The idea here is that a single group, or committee, will collect tons of data and attempt to define the various cell types. These cell types will then serve as a reference for all of science.

Let me dig a bit into each of these strategies.

Every scientist for themself

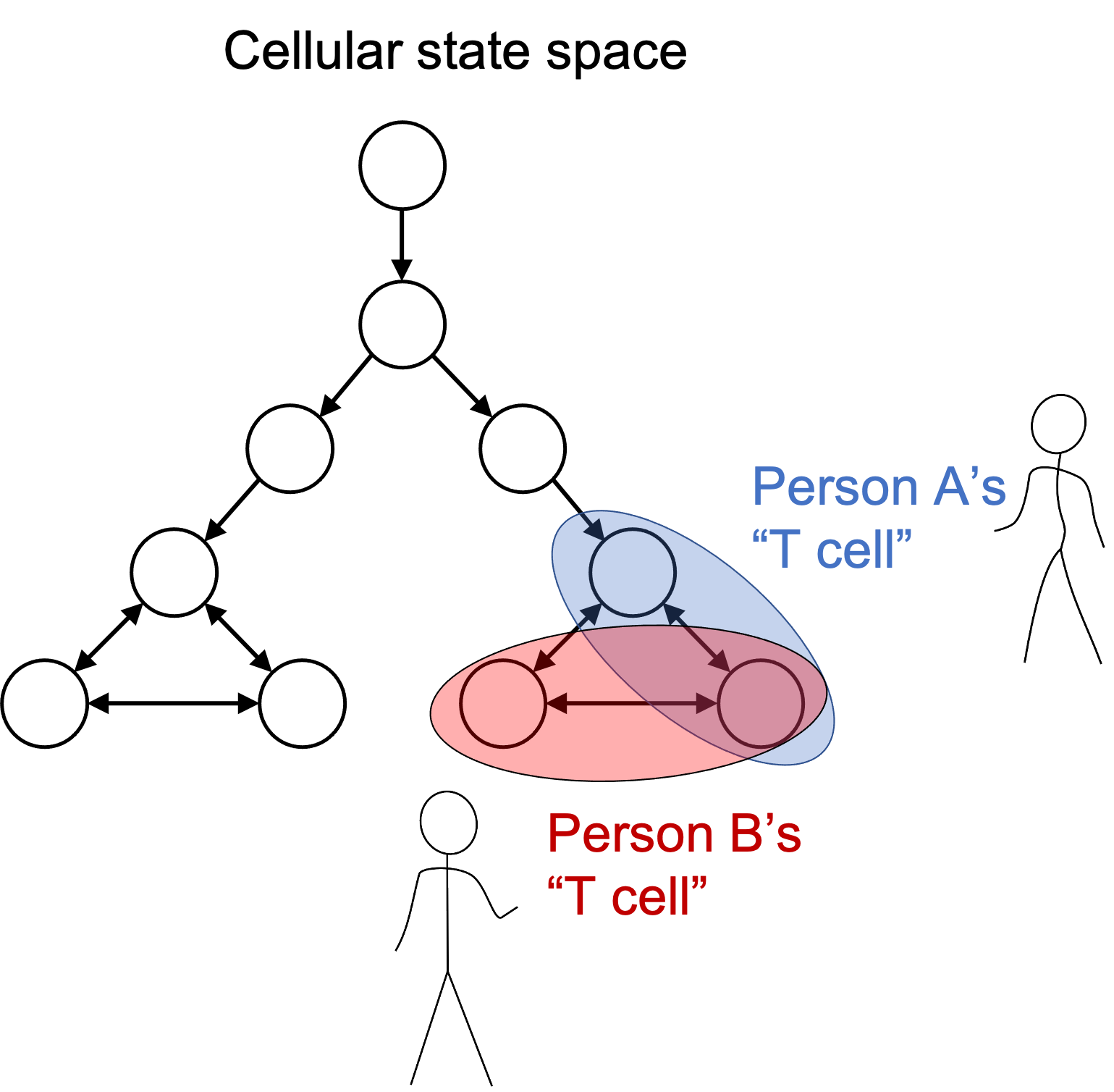

This is more or less the current state of affairs (minus the whole cellular state space framework). That is, each scientist has some unique definition of a cell type that may vary, perhaps slightly, with other scientist’s who uses that same cell type name. In the cellular state space framework, this scenario looks something like the following:

The benefit to this approach is that there is no need to come to a consenus on how to define a particular cell type. Just pick your own! However, without a common language for defining the cell states that they are using to define their cell types, this framework can easily suffer from the problem that two scientists might be using the same term to discuss two different cell types! This happens all the time. For example, when two scientists use two different sets of marker genes to label cell types in a single-cell RNA-seq dataset they are likely choosing different subsets of the cellular state space. Just take a look at the CellMarker database, a database of literature curated marker genes and you will see that there are often multiple sets of marker genes used to define the same cell type. In computer science parlance, the cell type names are overloaded.

Garnett is a cell type classification tool that, in some sense, embraces this idea. They have a model zoo where you can deposit your pre-trained classifiers that have been trained on data that was labelled based on your own, personal cell type definitions. Moreover, they provide a markdown language in which you define your cell types, and your cell type hierarchy based on your own choice of marker genes.

Crowdsourcing

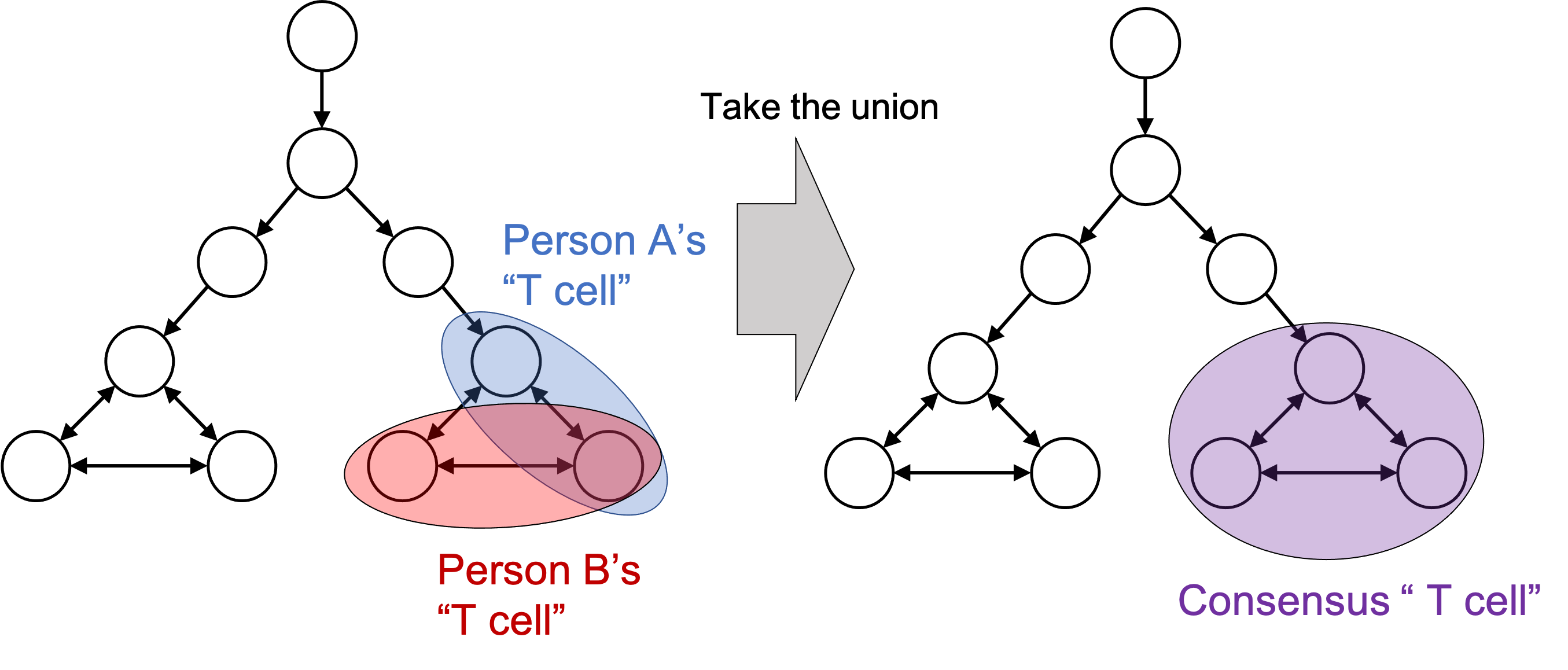

Here’s a less prevalent, but I think intriguing approach: let’s just take the union of all cellular states that have been used by a scientist and come to a consensus partition on the cellular state space. That is, if multiple scientific publications have slightly different definitions for “T cell”, let’s just use the union of all of them. This is depicted in the figure below:

I argue that cell type classification tools that are trained on public data take this approach. For example, our own tool, CellO, was trained on a collection of primary cell samples from the Sequence Read Archive. Another method that takes this approach is URSA. Importantly, the training labels used for training CellO and URSA are provided by the scientists who submitted their data. As discussed previously, they might have differing definitions for their cell types; however, this might be a good thing! We’re essentially crowdsourcing the definition of cell type to build a universal cell type classifier.

In fact, you can use such models to build up marker genes for defining each cell type. Because these marker genes are derived from models that are trained on an amalgamation of samples that might use slightly different definitions, one can view these definitions as sort of a consensus definition from the scientific community. You can check out CellO’s derived marker genes here.

One problem with this approach is that it is difficult to formalize the cell types defined in this way. Furthermore, it is prone to bad data, and thus, one might want to curate the samples one uses to create a consensus.

Central authority

Lastly, one can rely on a central authority to define cell types. This is the idea behind the Human Cell Atlas (HCA). The goal of the HCA is to bring together an international consortium of scientists to map out the cellular state space and come to agreed upon partitions of the state space from which one can then use for all of science. This strategy is the most ambitious! Of course, this is a massive undertaking, but if it works, would help to remove ambiguity and clarify our understanding of human biology.